24 Web scraping

24.1 Introduction

This chapter introduces you to the basics of web scraping with rvest. Web scraping is a very useful tool for extracting data from web pages. Some websites will offer an API, a set of structured HTTP requests that return data as JSON, which you handle using the techniques from Chapter 23. Where possible, you should use the API1, because typically it will give you more reliable data. Unfortunately, however, programming with web APIs is out of scope for this book. Instead, we are teaching scraping, a technique that works whether or not a site provides an API.

本章将向您介绍使用 rvest 进行网页抓取的基础知识。网页抓取(Web scraping)是从网页中提取数据的非常有用的工具。有些网站会提供 API,这是一组结构化的 HTTP 请求,以 JSON 格式返回数据,您可以使用 Chapter 23 中的技术来处理这些数据。在可能的情况下,您应该使用 API 1,因为它通常会为您提供更可靠的数据。然而,不幸的是,使用 Web API 进行编程超出了本书的范围。因此,我们教授的是抓取技术,无论网站是否提供 API,这种技术都适用。

In this chapter, we’ll first discuss the ethics and legalities of scraping before we dive into the basics of HTML. You’ll then learn the basics of CSS selectors to locate specific elements on the page, and how to use rvest functions to get data from text and attributes out of HTML and into R. We’ll then discuss some techniques to figure out what CSS selector you need for the page you’re scraping, before finishing up with a couple of case studies, and a brief discussion of dynamic websites.

在本章中,我们将在深入探讨 HTML 基础知识之前,首先讨论抓取的道德和法律问题。然后,您将学习 CSS 选择器的基础知识,以在页面上定位特定元素,以及如何使用 rvest 函数从 HTML 的文本和属性中提取数据并导入 R。接着,我们将讨论一些技巧,以确定您需要为正在抓取的页面使用哪种 CSS 选择器,最后通过几个案例研究,并简要讨论动态网站。

24.1.1 Prerequisites

In this chapter, we’ll focus on tools provided by rvest. rvest is a member of the tidyverse, but is not a core member so you’ll need to load it explicitly. We’ll also load the full tidyverse since we’ll find it generally useful working with the data we’ve scraped.

在本章中,我们将重点介绍 rvest 提供的工具。rvest 是 tidyverse 的成员,但不是核心成员,因此您需要显式加载它。我们还将加载完整的 tidyverse,因为在处理我们抓取的数据时,它通常会很有用。

24.2 Scraping ethics and legalities

Before we get started discussing the code you’ll need to perform web scraping, we need to talk about whether it’s legal and ethical for you to do so. Overall, the situation is complicated with regards to both of these.

在我们开始讨论执行网页抓取所需的代码之前,我们需要谈谈这样做是否合法和道德。总的来说,在这两个方面,情况都很复杂。

Legalities depend a lot on where you live. However, as a general principle, if the data is public, non-personal, and factual, you’re likely to be ok2. These three factors are important because they’re connected to the site’s terms and conditions, personally identifiable information, and copyright, as we’ll discuss below.

合法性在很大程度上取决于您居住的地方。然而,作为一般原则,如果数据是公开的、非个人的和事实性的,您很可能是可以的2。这三个因素很重要,因为它们与网站的服务条款、个人身份信息和版权有关,我们将在下面讨论。

If the data isn’t public, non-personal, or factual or you’re scraping the data specifically to make money with it, you’ll need to talk to a lawyer. In any case, you should be respectful of the resources of the server hosting the pages you are scraping. Most importantly, this means that if you’re scraping many pages, you should make sure to wait a little between each request. One easy way to do so is to use the polite package by Dmytro Perepolkin. It will automatically pause between requests and cache the results so you never ask for the same page twice.

如果数据不是公开的、非个人的或事实性的,或者您抓取数据是专门为了赚钱,那么您需要咨询律师。在任何情况下,您都应该尊重托管您正在抓取的页面的服务器资源。最重要的是,这意味着如果您要抓取许多页面,您应该确保在每个请求之间稍作等待。一个简单的方法是使用 Dmytro Perepolkin 的 polite 包。它会自动在请求之间暂停,并缓存结果,这样您就永远不会两次请求同一个页面。

24.2.1 Terms of service

If you look closely, you’ll find many websites include a “terms and conditions” or “terms of service” link somewhere on the page, and if you read that page closely you’ll often discover that the site specifically prohibits web scraping. These pages tend to be a legal land grab where companies make very broad claims. It’s polite to respect these terms of service where possible, but take any claims with a grain of salt.

如果您仔细查看,您会发现许多网站在页面的某个地方包含“条款和条件”或“服务条款”的链接,如果您仔细阅读该页面,您通常会发现该网站明确禁止网页抓取。这些页面往往是公司提出非常宽泛主张的法律圈地。在可能的情况下,尊重这些服务条款是礼貌的,但对任何主张都要持保留态度。

US courts have generally found that simply putting the terms of service in the footer of the website isn’t sufficient for you to be bound by them, e.g., HiQ Labs v. LinkedIn. Generally, to be bound to the terms of service, you must have taken some explicit action like creating an account or checking a box. This is why whether or not the data is public is important; if you don’t need an account to access them, it is unlikely that you are bound to the terms of service. Note, however, the situation is rather different in Europe where courts have found that terms of service are enforceable even if you don’t explicitly agree to them.

美国法院通常认为,仅仅将服务条款放在网站页脚并不足以使您受其约束,例如 HiQ Labs v. LinkedIn。通常,要受服务条款的约束,您必须采取一些明确的行动,如创建帐户或勾选复选框。这就是为什么数据是否公开很重要的原因;如果您不需要帐户即可访问它们,那么您就不太可能受服务条款的约束。但请注意,在欧洲情况有所不同,法院认为即使您没有明确同意,服务条款也是可强制执行的。

24.2.2 Personally identifiable information

Even if the data is public, you should be extremely careful about scraping personally identifiable information like names, email addresses, phone numbers, dates of birth, etc. Europe has particularly strict laws about the collection or storage of such data (GDPR), and regardless of where you live you’re likely to be entering an ethical quagmire. For example, in 2016, a group of researchers scraped public profile information (e.g., usernames, age, gender, location, etc.) about 70,000 people on the dating site OkCupid and they publicly released these data without any attempts for anonymization. While the researchers felt that there was nothing wrong with this since the data were already public, this work was widely condemned due to ethics concerns around identifiability of users whose information was released in the dataset. If your work involves scraping personally identifiable information, we strongly recommend reading about the OkCupid study3 as well as similar studies with questionable research ethics involving the acquisition and release of personally identifiable information.

即使数据是公开的,您在抓取姓名、电子邮件地址、电话号码、出生日期等个人身份信息时也应极其谨慎。欧洲对这类数据的收集或存储有特别严格的法律(GDPR),无论您住在哪里,您都可能陷入道德困境。例如,2016年,一群研究人员从交友网站 OkCupid 上抓取了约 70,000 人的公开个人资料信息(如用户名、年龄、性别、地点等),并在未进行任何匿名化处理的情况下公开发布了这些数据。尽管研究人员认为这样做没有错,因为数据已经是公开的,但这项工作因涉及数据集中用户信息的可识别性而受到广泛谴责。如果您的工作涉及抓取个人身份信息,我们强烈建议您阅读关于 OkCupid 研究的资料3,以及涉及获取和发布个人身份信息存在可疑研究伦理的类似研究。

24.2.3 Copyright

Finally, you also need to worry about copyright law. Copyright law is complicated, but it’s worth taking a look at the US law which describes exactly what’s protected: “[…] original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, […]”. It then goes on to describe specific categories that it applies like literary works, musical works, motion pictures and more. Notably absent from copyright protection are data. This means that as long as you limit your scraping to facts, copyright protection does not apply. (But note that Europe has a separate “sui generis” right that protects databases.)

最后,您还需要担心版权法。版权法很复杂,但值得一看的是美国法律,它确切地描述了受保护的内容:“[…] 固定在任何有形表达媒介上的原创作者作品 […]”。然后它继续描述了其适用的具体类别,如文学作品、音乐作品、电影等。值得注意的是,数据不在版权保护之列。这意味着,只要您将抓取范围限制在事实上,版权保护就不适用。(但请注意,欧洲有一项单独的“数据库权”(sui generis)来保护数据库。)

As a brief example, in the US, lists of ingredients and instructions are not copyrightable, so copyright can not be used to protect a recipe. But if that list of recipes is accompanied by substantial novel literary content, that is copyrightable. This is why when you’re looking for a recipe on the internet there’s always so much content beforehand.

举个简短的例子,在美国,配料清单和说明是不受版权保护的,因此版权不能用来保护食谱。但如果那份食谱清单附有大量新颖的文学内容,那么这些内容就是受版权保护的。这就是为什么当您在网上查找食谱时,总会先看到那么多内容。

If you do need to scrape original content (like text or images), you may still be protected under the doctrine of fair use. Fair use is not a hard and fast rule, but weighs up a number of factors. It’s more likely to apply if you are collecting the data for research or non-commercial purposes and if you limit what you scrape to just what you need.

如果您确实需要抓取原创内容(如文本或图像),您可能仍然受到合理使用原则的保护。合理使用不是一成不变的规则,而是权衡多种因素的结果。如果您是为研究或非商业目的收集数据,并且只抓取您需要的内容,那么它就更有可能适用。

24.3 HTML basics

To scrape webpages, you need to first understand a little bit about HTML, the language that describes web pages. HTML stands for HyperText Markup Language and looks something like this:

要抓取网页,您首先需要了解一些关于 HTML 的知识,这是一种描述网页的语言。HTML 是超文本标记语言(HyperText Markup Language)的缩写,看起来像这样:

<html>

<head>

<title>Page title</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1 id='first'>A heading</h1>

<p>Some text & <b>some bold text.</b></p>

<img src='myimg.png' width='100' height='100'>

</body>HTML has a hierarchical structure formed by elements which consist of a start tag (e.g., <tag>), optional attributes (id='first'), an end tag4 (like </tag>), and contents (everything in between the start and end tag).

HTML 具有由元素(elements)构成的层次结构,元素由开始标签(例如 <tag>)、可选的属性(attributes)(例如 id='first')、结束标签4(例如 </tag>)和内容(contents)(开始和结束标签之间的所有内容)组成。

Since < and > are used for start and end tags, you can’t write them directly. Instead you have to use the HTML escapes > (greater than) and < (less than). And since those escapes use &, if you want a literal ampersand you have to escape it as &. There are a wide range of possible HTML escapes but you don’t need to worry about them too much because rvest automatically handles them for you.

由于 < 和 > 用于开始和结束标签,因此不能直接书写它们。您必须使用 HTML 转义符(escapes),即 >(大于)和 <(小于)。又因为这些转义符使用了 &,所以如果您想表示一个字面意义上的与号(ampersand),就必须将其转义为 &。HTML 有很多种可能的转义符,但您不必太过担心,因为 rvest 会自动为您处理。

Web scraping is possible because most pages that contain data that you want to scrape generally have a consistent structure.

网页抓取之所以可行,是因为大多数包含您想要抓取数据地网页通常具有一致的结构。

24.3.1 Elements

There are over 100 HTML elements. Some of the most important are:

HTML 元素超过 100 种。其中一些最重要的包括:

Every HTML page must be in an

<html>element, and it must have two children:<head>, which contains document metadata like the page title, and<body>, which contains the content you see in the browser.

每个 HTML 页面都必须位于一个<html>元素中,并且它必须有两个子元素:<head>,包含文档元数据,如页面标题;以及<body>,包含您在浏览器中看到的内容。Block tags like

<h1>(heading 1),<section>(section),<p>(paragraph), and<ol>(ordered list) form the overall structure of the page.

块级标签,如<h1>(一级标题)、<section>(节)、<p>(段落)和<ol>(有序列表),构成了页面的整体结构。Inline tags like

<b>(bold),<i>(italics), and<a>(link) format text inside block tags.

内联标签,如<b>(粗体)、<i>(斜体)和<a>(链接),用于格式化块级标签内的文本。

If you encounter a tag that you’ve never seen before, you can find out what it does with a little googling. Another good place to start are the MDN Web Docs which describe just about every aspect of web programming.

如果您遇到一个从未见过的标签,可以通过 Google 搜索来了解它的作用。另一个很好的起点是 MDN Web Docs,它几乎描述了网页编程的方方面面。

Most elements can have content in between their start and end tags. This content can either be text or more elements. For example, the following HTML contains paragraph of text, with one word in bold.

大多数元素都可以在其开始和结束标签之间包含内容。这个内容可以是文本,也可以是更多的元素。例如,下面的 HTML 包含一个文本段落,其中一个词是粗体。

<p>

Hi! My <b>name</b> is Hadley.

</p>The children are the elements it contains, so the <p> element above has one child, the <b> element. The <b> element has no children, but it does have contents (the text “name”).

子元素(children)是它所包含的元素,所以上面 <p> 元素有一个子元素,即 <b> 元素。<b> 元素没有子元素,但它有内容(文本“name”)。

24.3.2 Attributes

Tags can have named attributes which look like name1='value1' name2='value2'. Two of the most important attributes are id and class, which are used in conjunction with CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) to control the visual appearance of the page. These are often useful when scraping data off a page. Attributes are also used to record the destination of links (the href attribute of <a> elements) and the source of images (the src attribute of the <img> element).

标签可以有名为属性(attributes)的参数,其形式如 name1='value1' name2='value2'。其中最重要的两个属性是 id 和 class,它们与 CSS(层叠样式表)结合使用,以控制页面的视觉外观。在从页面抓取数据时,这些属性通常很有用。属性还用于记录链接的目的地(<a> 元素的 href 属性)和图像的来源(<img> 元素的 src 属性)。

24.4 Extracting data

To get started scraping, you’ll need the URL of the page you want to scrape, which you can usually copy from your web browser. You’ll then need to read the HTML for that page into R with read_html(). This returns an xml_document5 object which you’ll then manipulate using rvest functions:

要开始抓取,您需要目标页面的 URL,通常可以从您的网络浏览器中复制。然后,您需要使用 read_html() 将该页面的 HTML 读入 R。这将返回一个 xml_document5 对象,您将使用 rvest 函数对其进行操作:

html <- read_html("http://rvest.tidyverse.org/")

html

#> {html_document}

#> <html lang="en">

#> [1] <head>\n<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UT ...

#> [2] <body>\n <a href="#container" class="visually-hidden-focusable">Ski ...rvest also includes a function that lets you write HTML inline. We’ll use this a bunch in this chapter as we teach how the various rvest functions work with simple examples.

rvest 还包含一个允许您内联编写 HTML 的函数。在本章中,我们将大量使用它,通过简单的例子来教授各种 rvest 函数的工作方式。

html <- minimal_html("

<p>This is a paragraph</p>

<ul>

<li>This is a bulleted list</li>

</ul>

")

html

#> {html_document}

#> <html>

#> [1] <head>\n<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UT ...

#> [2] <body>\n<p>This is a paragraph</p>\n <ul>\n<li>This is a bulleted lis ...Now that you have the HTML in R, it’s time to extract the data of interest. You’ll first learn about the CSS selectors that allow you to identify the elements of interest and the rvest functions that you can use to extract data from them. Then we’ll briefly cover HTML tables, which have some special tools.

现在您已经在 R 中获得了 HTML,是时候提取感兴趣的数据了。您将首先了解 CSS 选择器,它允许您识别感兴趣的元素,以及可以用来从中提取数据的 rvest 函数。然后我们将简要介绍 HTML 表格,它有一些特殊的工具。

24.4.1 Find elements

CSS is short for cascading style sheets, and is a tool for defining the visual styling of HTML documents. CSS includes a miniature language for selecting elements on a page called CSS selectors. CSS selectors define patterns for locating HTML elements, and are useful for scraping because they provide a concise way of describing which elements you want to extract.

CSS 是层叠样式表(cascading style sheets)的缩写,是用于定义 HTML 文档视觉样式的工具。CSS 包含一种用于在页面上选择元素的微型语言,称为 CSS 选择器(CSS selectors)。CSS 选择器定义了定位 HTML 元素的模式,在抓取数据时非常有用,因为它们提供了一种简洁的方式来描述您想要提取的元素。

We’ll come back to CSS selectors in more detail in Section 24.5, but luckily you can get a long way with just three:

我们将在 Section 24.5 中更详细地回到 CSS 选择器,但幸运的是,仅用以下三个就可以走得很远:

pselects all<p>elements.p选择所有的<p>元素。.titleselects all elements withclass“title”..title选择所有class为 “title” 的元素。#titleselects the element with theidattribute that equals “title”. Id attributes must be unique within a document, so this will only ever select a single element.#title选择id属性等于 “title” 的元素。Id 属性在文档中必须是唯一的,所以这只会选择一个元素。

Let’s try out these selectors with a simple example:

让我们用一个简单的例子来试试这些选择器:

html <- minimal_html("

<h1>This is a heading</h1>

<p id='first'>This is a paragraph</p>

<p class='important'>This is an important paragraph</p>

")Use html_elements() to find all elements that match the selector:

使用 html_elements() 查找所有匹配选择器的元素:

html |> html_elements("p")

#> {xml_nodeset (2)}

#> [1] <p id="first">This is a paragraph</p>

#> [2] <p class="important">This is an important paragraph</p>

html |> html_elements(".important")

#> {xml_nodeset (1)}

#> [1] <p class="important">This is an important paragraph</p>

html |> html_elements("#first")

#> {xml_nodeset (1)}

#> [1] <p id="first">This is a paragraph</p>Another important function is html_element() which always returns the same number of outputs as inputs. If you apply it to a whole document it’ll give you the first match:

另一个重要的函数是 html_element(),它总是返回与输入相同数量的输出。如果将其应用于整个文档,它将给出第一个匹配项:

html |> html_element("p")

#> {html_node}

#> <p id="first">There’s an important difference between html_element() and html_elements() when you use a selector that doesn’t match any elements. html_elements() returns a vector of length 0, where html_element() returns a missing value. This will be important shortly.

当您使用一个不匹配任何元素的选择器时,html_element() 和 html_elements() 之间有一个重要的区别。html_elements() 返回一个长度为 0 的向量,而 html_element() 返回一个缺失值。这一点很快就会变得很重要。

html |> html_elements("b")

#> {xml_nodeset (0)}

html |> html_element("b")

#> {xml_missing}

#> <NA>24.4.2 Nesting selections

In most cases, you’ll use html_elements() and html_element() together, typically using html_elements() to identify elements that will become observations then using html_element() to find elements that will become variables. Let’s see this in action using a simple example. Here we have an unordered list (<ul>) where each list item (<li>) contains some information about four characters from StarWars:

在大多数情况下,您会同时使用 html_elements() 和 html_element(),通常使用 html_elements() 来识别将成为观测值的元素,然后使用 html_element() 来查找将成为变量的元素。让我们通过一个简单的例子来看看它的实际应用。这里我们有一个无序列表(<ul>),其中每个列表项(<li>)都包含有关《星球大战》中四个角色的一些信息:

html <- minimal_html("

<ul>

<li><b>C-3PO</b> is a <i>droid</i> that weighs <span class='weight'>167 kg</span></li>

<li><b>R4-P17</b> is a <i>droid</i></li>

<li><b>R2-D2</b> is a <i>droid</i> that weighs <span class='weight'>96 kg</span></li>

<li><b>Yoda</b> weighs <span class='weight'>66 kg</span></li>

</ul>

")We can use html_elements() to make a vector where each element corresponds to a different character:

我们可以使用 html_elements() 创建一个向量,其中每个元素对应一个不同的角色:

characters <- html |> html_elements("li")

characters

#> {xml_nodeset (4)}

#> [1] <li>\n<b>C-3PO</b> is a <i>droid</i> that weighs <span class="weight"> ...

#> [2] <li>\n<b>R4-P17</b> is a <i>droid</i>\n</li>

#> [3] <li>\n<b>R2-D2</b> is a <i>droid</i> that weighs <span class="weight"> ...

#> [4] <li>\n<b>Yoda</b> weighs <span class="weight">66 kg</span>\n</li>To extract the name of each character, we use html_element(), because when applied to the output of html_elements() it’s guaranteed to return one response per element:

要提取每个角色的名字,我们使用 html_element(),因为当它应用于 html_elements() 的输出时,可以保证为每个元素返回一个响应:

characters |> html_element("b")

#> {xml_nodeset (4)}

#> [1] <b>C-3PO</b>

#> [2] <b>R4-P17</b>

#> [3] <b>R2-D2</b>

#> [4] <b>Yoda</b>The distinction between html_element() and html_elements() isn’t important for name, but it is important for weight. We want to get one weight for each character, even if there’s no weight <span>. That’s what html_element() does:

对于名字来说,html_element() 和 html_elements() 之间的区别并不重要,但对于体重来说,这个区别很重要。我们希望为每个角色获取一个体重,即使没有体重 <span> 标签。这正是 html_element() 所做的:

characters |> html_element(".weight")

#> {xml_nodeset (4)}

#> [1] <span class="weight">167 kg</span>

#> [2] NA

#> [3] <span class="weight">96 kg</span>

#> [4] <span class="weight">66 kg</span>html_elements() finds all weight <span>s that are children of characters. There’s only three of these, so we lose the connection between names and weights:html_elements() 会找到 characters 的所有子元素中的体重 <span>。这里只有三个,所以我们失去了名字和体重之间的联系:

characters |> html_elements(".weight")

#> {xml_nodeset (3)}

#> [1] <span class="weight">167 kg</span>

#> [2] <span class="weight">96 kg</span>

#> [3] <span class="weight">66 kg</span>Now that you’ve selected the elements of interest, you’ll need to extract the data, either from the text contents or some attributes.

既然您已经选择了感兴趣的元素,接下来就需要从文本内容或某些属性中提取数据。

24.4.3 Text and attributes

html_text2()6 extracts the plain text contents of an HTML element:html_text2()6 提取 HTML 元素的纯文本内容:

characters |>

html_element("b") |>

html_text2()

#> [1] "C-3PO" "R4-P17" "R2-D2" "Yoda"

characters |>

html_element(".weight") |>

html_text2()

#> [1] "167 kg" NA "96 kg" "66 kg"Note that any escapes will be automatically handled; you’ll only ever see HTML escapes in the source HTML, not in the data returned by rvest.

请注意,任何转义字符都会被自动处理;你只会在源 HTML 中看到 HTML 转义字符,而不会在 rvest 返回的数据中看到。

html_attr() extracts data from attributes:html_attr() 从属性中提取数据:

html <- minimal_html("

<p><a href='https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cat'>cats</a></p>

<p><a href='https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dog'>dogs</a></p>

")

html |>

html_elements("p") |>

html_element("a") |>

html_attr("href")

#> [1] "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cat" "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dog"html_attr() always returns a string, so if you’re extracting numbers or dates, you’ll need to do some post-processing.html_attr() 总是返回一个字符串,所以如果你要提取数字或日期,就需要进行一些后处理。

24.4.4 Tables

If you’re lucky, your data will be already stored in an HTML table, and it’ll be a matter of just reading it from that table. It’s usually straightforward to recognize a table in your browser: it’ll have a rectangular structure of rows and columns, and you can copy and paste it into a tool like Excel.

如果你幸运的话,你的数据可能已经存储在 HTML 表格中,那么问题就简化为从该表格中读取数据。在浏览器中识别表格通常很简单:它会有一个由行和列组成的矩形结构,你可以将其复制并粘贴到像 Excel 这样的工具中。

HTML tables are built up from four main elements: <table>, <tr> (table row), <th> (table heading), and <td> (table data). Here’s a simple HTML table with two columns and three rows:

HTML 表格由四个主要元素构成:<table>、<tr> (table row,表格行)、<th> (table heading,表头) 和 <td> (table data,表格数据)。下面是一个包含两列三行的简单 HTML 表格:

html <- minimal_html("

<table class='mytable'>

<tr><th>x</th> <th>y</th></tr>

<tr><td>1.5</td> <td>2.7</td></tr>

<tr><td>4.9</td> <td>1.3</td></tr>

<tr><td>7.2</td> <td>8.1</td></tr>

</table>

")rvest provides a function that knows how to read this sort of data: html_table(). It returns a list containing one tibble for each table found on the page. Use html_element() to identify the table you want to extract:

rvest 提供了一个知道如何读取这类数据的函数:html_table()。它返回一个列表,其中包含页面上找到的每个表格对应的一个 tibble。使用 html_element() 来识别你想要提取的表格:

html |>

html_element(".mytable") |>

html_table()

#> # A tibble: 3 × 2

#> x y

#> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 1.5 2.7

#> 2 4.9 1.3

#> 3 7.2 8.1Note that x and y have automatically been converted to numbers. This automatic conversion doesn’t always work, so in more complex scenarios you may want to turn it off with convert = FALSE and then do your own conversion.

注意 x 和 y 已被自动转换为数字。这种自动转换并不总是有效,因此在更复杂的场景中,你可能需要使用 convert = FALSE 将其关闭,然后自己进行转换。

24.5 Finding the right selectors

Figuring out the selector you need for your data is typically the hardest part of the problem. You’ll often need to do some experimenting to find a selector that is both specific (i.e. it doesn’t select things you don’t care about) and sensitive (i.e. it does select everything you care about). Lots of trial and error is a normal part of the process! There are two main tools that are available to help you with this process: SelectorGadget and your browser’s developer tools.

找出数据所需的选择器通常是问题中最困难的部分。你通常需要进行一些实验,以找到一个既具体 (specific)(即它不会选择你不在乎的东西)又敏感 (sensitive)(即它确实选择了你关心的所有东西)的选择器。大量的反复试验是这个过程的正常部分!有两个主要工具可以帮助你完成这个过程:SelectorGadget 和你浏览器的开发者工具。

SelectorGadget is a javascript bookmarklet that automatically generates CSS selectors based on the positive and negative examples that you provide. It doesn’t always work, but when it does, it’s magic! You can learn how to install and use SelectorGadget either by reading https://rvest.tidyverse.org/articles/selectorgadget.html or watching Mine’s video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PetWV5g1Xsc.

SelectorGadget 是一个 javascript 书签工具,它可以根据你提供的正面和负面示例自动生成 CSS 选择器。它并不总是有效,但一旦有效,效果就如同魔法!你可以通过阅读 https://rvest.tidyverse.org/articles/selectorgadget.html 或观看 Mine 在 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PetWV5g1Xsc 上的视频来学习如何安装和使用 SelectorGadget。

Every modern browser comes with some toolkit for developers, but we recommend Chrome, even if it isn’t your regular browser: its web developer tools are some of the best and they’re immediately available. Right click on an element on the page and click Inspect. This will open an expandable view of the complete HTML page, centered on the element that you just clicked. You can use this to explore the page and get a sense of what selectors might work. Pay particular attention to the class and id attributes, since these are often used to form the visual structure of the page, and hence make for good tools to extract the data that you’re looking for.

每个现代浏览器都带有一些面向开发者的工具包,但我们推荐使用 Chrome,即使它不是你的常用浏览器:它的 Web 开发者工具是最好的之一,而且可以立即使用。在页面上的一个元素上右键单击,然后点击 Inspect (检查)。这将打开一个可展开的完整 HTML 页面视图,并以你刚刚点击的元素为中心。你可以用它来探索页面,并了解哪些选择器可能有效。要特别注意 class 和 id 属性,因为它们通常用于构成页面的视觉结构,因此是提取你所寻找数据的好工具。

Inside the Elements view, you can also right click on an element and choose Copy as Selector to generate a selector that will uniquely identify the element of interest.

在“元素”(Elements) 视图中,你还可以在一个元素上右键单击并选择 Copy as Selector (复制为选择器),以生成一个能唯一标识目标元素的选择器。

If either SelectorGadget or Chrome DevTools have generated a CSS selector that you don’t understand, try Selectors Explained which translates CSS selectors into plain English. If you find yourself doing this a lot, you might want to learn more about CSS selectors generally. We recommend starting with the fun CSS dinner tutorial and then referring to the MDN web docs.

如果 SelectorGadget 或 Chrome 开发者工具生成了你看不懂的 CSS 选择器,可以试试 Selectors Explained,它能将 CSS 选择器翻译成通俗易懂的英语。如果你发现自己经常这样做,你可能需要更全面地学习 CSS 选择器。我们推荐从有趣的 CSS dinner 教程开始,然后参考 MDN web docs。

24.6 Putting it all together

Let’s put this all together to scrape some websites. There’s some risk that these examples may no longer work when you run them — that’s the fundamental challenge of web scraping; if the structure of the site changes, then you’ll have to change your scraping code.

让我们把所有这些整合起来,去爬取一些网站。当你运行这些示例时,它们可能不再有效,这存在一定的风险——这是网络爬取的根本挑战;如果网站的结构发生变化,你就必须修改你的爬取代码。

24.6.1 StarWars

rvest includes a very simple example in vignette("starwars"). This is a simple page with minimal HTML so it’s a good place to start. I’d encourage you to navigate to that page now and use “Inspect Element” to inspect one of the headings that’s the title of a Star Wars movie. Use the keyboard or mouse to explore the hierarchy of the HTML and see if you can get a sense of the shared structure used by each movie.

rvest 在 vignette("starwars") 中包含了一个非常简单的例子。这是一个 HTML 极简的简单页面,所以是一个很好的起点。我鼓励你现在就导航到那个页面,并使用“检查元素”(Inspect Element) 来检查其中一个作为星球大战电影标题的标题。使用键盘或鼠标来探索 HTML 的层次结构,看看你是否能了解每部电影所使用的共享结构。

You should be able to see that each movie has a shared structure that looks like this:

你应该能够看到每部电影都有一个共享的结构,看起来像这样:

<section>

<h2 data-id="1">The Phantom Menace</h2>

<p>Released: 1999-05-19</p>

<p>Director: <span class="director">George Lucas</span></p>

<div class="crawl">

<p>...</p>

<p>...</p>

<p>...</p>

</div>

</section>Our goal is to turn this data into a 7 row data frame with variables title, year, director, and intro. We’ll start by reading the HTML and extracting all the <section> elements:

我们的目标是将这些数据转换成一个包含 title、year、director 和 intro 变量的 7 行数据框。我们将从读取 HTML 并提取所有 <section> 元素开始:

url <- "https://rvest.tidyverse.org/articles/starwars.html"

html <- read_html(url)

section <- html |> html_elements("section")

section

#> {xml_nodeset (7)}

#> [1] <section><h2 data-id="1">\nThe Phantom Menace\n</h2>\n<p>\nReleased: 1 ...

#> [2] <section><h2 data-id="2">\nAttack of the Clones\n</h2>\n<p>\nReleased: ...

#> [3] <section><h2 data-id="3">\nRevenge of the Sith\n</h2>\n<p>\nReleased: ...

#> [4] <section><h2 data-id="4">\nA New Hope\n</h2>\n<p>\nReleased: 1977-05-2 ...

#> [5] <section><h2 data-id="5">\nThe Empire Strikes Back\n</h2>\n<p>\nReleas ...

#> [6] <section><h2 data-id="6">\nReturn of the Jedi\n</h2>\n<p>\nReleased: 1 ...

#> [7] <section><h2 data-id="7">\nThe Force Awakens\n</h2>\n<p>\nReleased: 20 ...This retrieves seven elements matching the seven movies found on that page, suggesting that using section as a selector is good. Extracting the individual elements is straightforward since the data is always found in the text. It’s just a matter of finding the right selector:

这段代码检索到七个元素,与页面上找到的七部电影相匹配,这表明使用 section 作为选择器是很好的。提取单个元素很简单,因为数据总是在文本中找到。这只是找到正确选择器的问题:

section |> html_element("h2") |> html_text2()

#> [1] "The Phantom Menace" "Attack of the Clones"

#> [3] "Revenge of the Sith" "A New Hope"

#> [5] "The Empire Strikes Back" "Return of the Jedi"

#> [7] "The Force Awakens"

section |> html_element(".director") |> html_text2()

#> [1] "George Lucas" "George Lucas" "George Lucas"

#> [4] "George Lucas" "Irvin Kershner" "Richard Marquand"

#> [7] "J. J. Abrams"Once we’ve done that for each component, we can wrap all the results up into a tibble:

为每个组件完成此操作后,我们可以将所有结果包装到一个 tibble 中:

tibble(

title = section |>

html_element("h2") |>

html_text2(),

released = section |>

html_element("p") |>

html_text2() |>

str_remove("Released: ") |>

parse_date(),

director = section |>

html_element(".director") |>

html_text2(),

intro = section |>

html_element(".crawl") |>

html_text2()

)

#> # A tibble: 7 × 4

#> title released director intro

#> <chr> <date> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 The Phantom Menace 1999-05-19 George Lucas "Turmoil has engulfed …

#> 2 Attack of the Clones 2002-05-16 George Lucas "There is unrest in th…

#> 3 Revenge of the Sith 2005-05-19 George Lucas "War! The Republic is …

#> 4 A New Hope 1977-05-25 George Lucas "It is a period of civ…

#> 5 The Empire Strikes Back 1980-05-17 Irvin Kershner "It is a dark time for…

#> 6 Return of the Jedi 1983-05-25 Richard Marquand "Luke Skywalker has re…

#> # ℹ 1 more rowWe did a little more processing of released to get a variable that will be easy to use later in our analysis.

我们对 released 进行了更多的处理,以得到一个在后续分析中更易于使用的变量。

24.6.2 IMDB top films

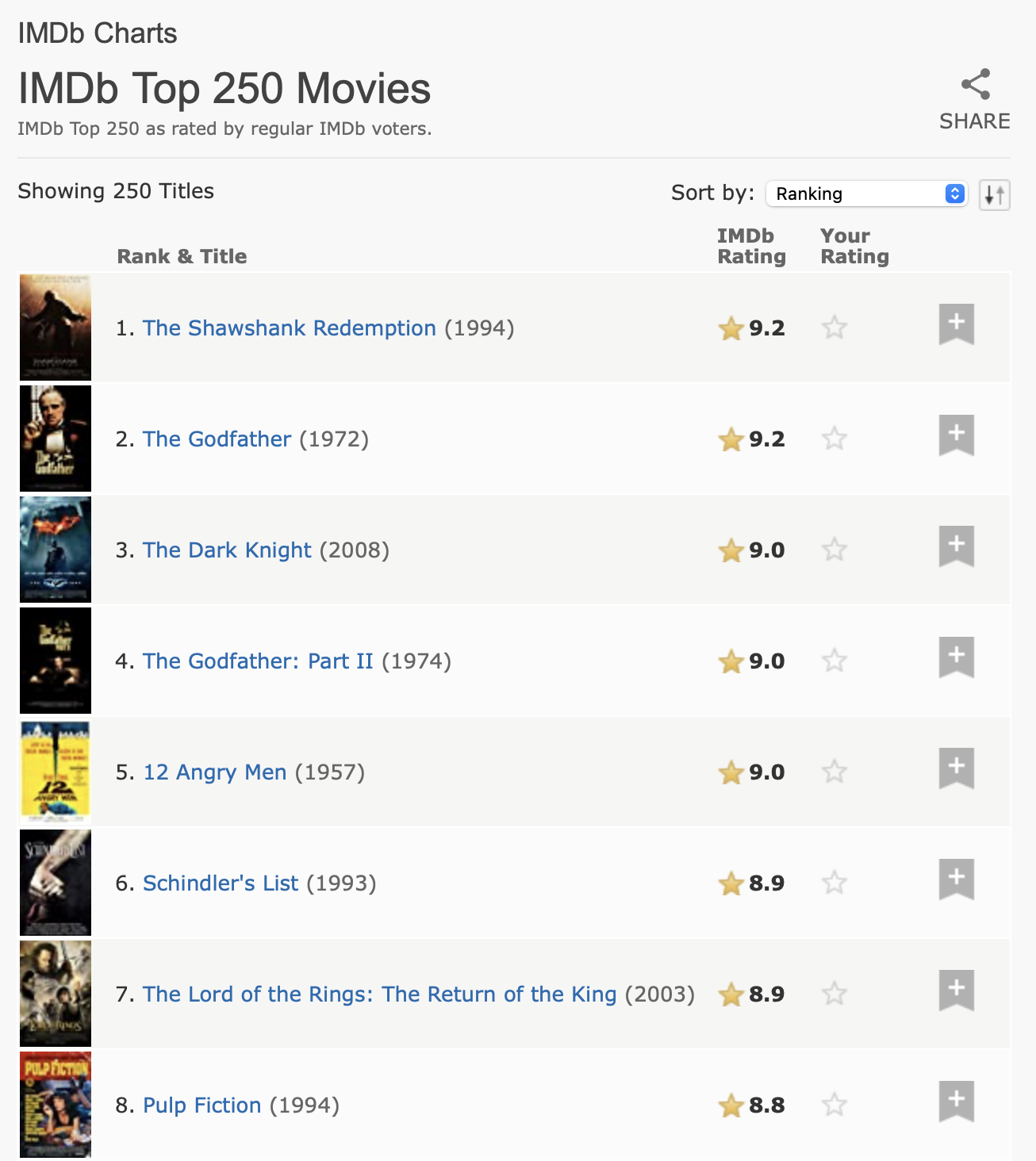

For our next task we’ll tackle something a little trickier, extracting the top 250 movies from the internet movie database (IMDb). At the time we wrote this chapter, the page looked like Figure 24.1.

在我们的下一个任务中,我们将处理一个稍微棘手的问题,即从互联网电影数据库 (IMDb) 中提取排名前 250 的电影。在我们撰写本章时,该页面的外观如 Figure 24.1 所示。

This data has a clear tabular structure so it’s worth starting with html_table():

这些数据具有清晰的表格结构,因此值得从 html_table() 开始:

url <- "https://web.archive.org/web/20220201012049/https://www.imdb.com/chart/top/"

html <- read_html(url)

table <- html |>

html_element("table") |>

html_table()

table

#> # A tibble: 250 × 5

#> `` `Rank & Title` `IMDb Rating` `Your Rating` ``

#> <lgl> <chr> <dbl> <chr> <lgl>

#> 1 NA "1.\n The Shawshank Redempt… 9.2 "12345678910\n… NA

#> 2 NA "2.\n The Godfather\n … 9.1 "12345678910\n… NA

#> 3 NA "3.\n The Godfather: Part I… 9 "12345678910\n… NA

#> 4 NA "4.\n The Dark Knight\n … 9 "12345678910\n… NA

#> 5 NA "5.\n 12 Angry Men\n … 8.9 "12345678910\n… NA

#> 6 NA "6.\n Schindler's List\n … 8.9 "12345678910\n… NA

#> # ℹ 244 more rowsThis includes a few empty columns, but overall does a good job of capturing the information from the table. However, we need to do some more processing to make it easier to use. First, we’ll rename the columns to be easier to work with, and remove the extraneous whitespace in rank and title. We will do this with select() (instead of rename()) to do the renaming and selecting of just these two columns in one step. Then we’ll remove the new lines and extra spaces, and then apply separate_wider_regex() (from Section 15.3.4) to pull out the title, year, and rank into their own variables.

这其中包含一些空列,但总体上很好地捕获了表格中的信息。然而,我们需要进行更多的处理以使其更易于使用。首先,我们将重命名列名以便于操作,并移除排名和标题中多余的空白。我们将使用 select() (而不是 rename()) 来一步完成重命名和仅选择这两列的操作。然后,我们将移除换行符和多余的空格,接着应用 separate_wider_regex() (来自 Section 15.3.4) 将标题、年份和排名提取到各自的变量中。

ratings <- table |>

select(

rank_title_year = `Rank & Title`,

rating = `IMDb Rating`

) |>

mutate(

rank_title_year = str_replace_all(rank_title_year, "\n +", " ")

) |>

separate_wider_regex(

rank_title_year,

patterns = c(

rank = "\\d+", "\\. ",

title = ".+", " +\\(",

year = "\\d+", "\\)"

)

)

ratings

#> # A tibble: 250 × 4

#> rank title year rating

#> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 1 The Shawshank Redemption 1994 9.2

#> 2 2 The Godfather 1972 9.1

#> 3 3 The Godfather: Part II 1974 9

#> 4 4 The Dark Knight 2008 9

#> 5 5 12 Angry Men 1957 8.9

#> 6 6 Schindler's List 1993 8.9

#> # ℹ 244 more rowsEven in this case where most of the data comes from table cells, it’s still worth looking at the raw HTML. If you do so, you’ll discover that we can add a little extra data by using one of the attributes. This is one of the reasons it’s worth spending a little time spelunking the source of the page; you might find extra data, or might find a parsing route that’s slightly easier.

即使在这种大部分数据来自表格单元格的情况下,查看原始 HTML 仍然是值得的。如果你这样做,你会发现我们可以通过使用其中一个属性来添加一些额外的数据。这就是花点时间研究页面源代码的原因之一;你可能会发现额外的数据,或者找到一个稍微容易一些的解析路径。

html |>

html_elements("td strong") |>

head() |>

html_attr("title")

#> [1] "9.2 based on 2,536,415 user ratings"

#> [2] "9.1 based on 1,745,675 user ratings"

#> [3] "9.0 based on 1,211,032 user ratings"

#> [4] "9.0 based on 2,486,931 user ratings"

#> [5] "8.9 based on 749,563 user ratings"

#> [6] "8.9 based on 1,295,705 user ratings"We can combine this with the tabular data and again apply separate_wider_regex() to extract out the bit of data we care about:

我们可以将其与表格数据结合起来,并再次应用 separate_wider_regex() 来提取我们关心的那部分数据:

ratings |>

mutate(

rating_n = html |> html_elements("td strong") |> html_attr("title")

) |>

separate_wider_regex(

rating_n,

patterns = c(

"[0-9.]+ based on ",

number = "[0-9,]+",

" user ratings"

)

) |>

mutate(

number = parse_number(number)

)

#> # A tibble: 250 × 5

#> rank title year rating number

#> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 1 The Shawshank Redemption 1994 9.2 2536415

#> 2 2 The Godfather 1972 9.1 1745675

#> 3 3 The Godfather: Part II 1974 9 1211032

#> 4 4 The Dark Knight 2008 9 2486931

#> 5 5 12 Angry Men 1957 8.9 749563

#> 6 6 Schindler's List 1993 8.9 1295705

#> # ℹ 244 more rows24.7 Dynamic sites

So far we have focused on websites where html_elements() returns what you see in the browser and discussed how to parse what it returns and how to organize that information in tidy data frames. From time-to-time, however, you’ll hit a site where html_elements() and friends don’t return anything like what you see in the browser. In many cases, that’s because you’re trying to scrape a website that dynamically generates the content of the page with javascript. This doesn’t currently work with rvest, because rvest downloads the raw HTML and doesn’t run any javascript.

到目前为止,我们一直专注于那些 html_elements() 返回你在浏览器中看到的内容的网站,并讨论了如何解析其返回内容以及如何将这些信息组织成整洁的数据框。然而,你偶尔会遇到一个网站,其中 html_elements() 及其相关函数返回的内容与你在浏览器中看到的完全不同。在许多情况下,这是因为你试图爬取一个使用 javascript 动态生成页面内容的网站。这目前不适用于 rvest,因为 rvest 下载的是原始 HTML,不运行任何 javascript。

It’s still possible to scrape these types of sites, but rvest needs to use a more expensive process: fully simulating the web browser including running all javascript. This functionality is not available at the time of writing, but it’s something we’re actively working on and might be available by the time you read this. It uses the chromote package which actually runs the Chrome browser in the background, and gives you additional tools to interact with the site, like a human typing text and clicking buttons. Check out the rvest website for more details.

仍然可以爬取这类网站,但 rvest 需要使用一个更昂贵的过程:完全模拟网络浏览器,包括运行所有 javascript。在撰写本文时,此功能尚不可用,但这是我们正在积极开发的功能,当你阅读本文时可能已经可用。它使用 chromote 包,该包实际上在后台运行 Chrome 浏览器,并为你提供与网站交互的额外工具,就像人类输入文本和点击按钮一样。请查看 rvest 网站 以获取更多详细信息。

24.8 Summary

In this chapter, you’ve learned about the why, the why not, and the how of scraping data from web pages. First, you’ve learned about the basics of HTML and using CSS selectors to refer to specific elements, then you’ve learned about using the rvest package to get data out of HTML into R. We then demonstrated web scraping with two case studies: a simpler scenario on scraping data on StarWars films from the rvest package website and a more complex scenario on scraping the top 250 films from IMDB.

在本章中,你学习了从网页上爬取数据的原因、不应爬取的情况以及如何爬取。首先,你学习了 HTML 的基础知识和使用 CSS 选择器来引用特定元素,然后你学习了使用 rvest 包将数据从 HTML 中提取到 R 中。接着,我们通过两个案例研究演示了网络爬取:一个是在 rvest 包网站上爬取星球大战电影数据的较简单场景,另一个是在 IMDB 上爬取排名前 250 部电影的较复杂场景。

Technical details of scraping data off the web can be complex, particularly when dealing with sites, however legal and ethical considerations can be even more complex. It’s important for you to educate yourself about both of these before setting out to scrape data.

从网络上爬取数据的技术细节可能很复杂,尤其是在处理网站时,然而法律和道德方面的考虑可能更为复杂。在开始爬取数据之前,对这两方面进行自我教育是非常重要的。

This brings us to the end of the import part of the book where you’ve learned techniques to get data from where it lives (spreadsheets, databases, JSON files, and web sites) into a tidy form in R. Now it’s time to turn our sights to a new topic: making the most of R as a programming language.

这就结束了本书的导入部分,你已经学习了从数据所在之处(电子表格、数据库、JSON 文件和网站)获取数据并将其整理成 R 中整洁形式的技术。现在是时候将我们的目光转向一个新主题:充分利用 R 作为一种编程语言。

And many popular APIs already have CRAN packages that wrap them, so start with a little research first!↩︎

Obviously we’re not lawyers, and this is not legal advice. But this is the best summary we can give having read a bunch about this topic.↩︎

One example of an article on the OkCupid study was published by Wired, https://www.wired.com/2016/05/okcupid-study-reveals-perils-big-data-science.↩︎

A number of tags (including

<p>and<li>)don’t require end tags, but we think it’s best to include them because it makes seeing the structure of the HTML a little easier.↩︎This class comes from the xml2 package. xml2 is a low-level package that rvest builds on top of.↩︎

rvest also provides

html_text()but you should almost always usehtml_text2()since it does a better job of converting nested HTML to text.↩︎