14 Strings

14.1 Introduction

So far, you’ve used a bunch of strings without learning much about the details. Now it’s time to dive into them, learn what makes strings tick, and master some of the powerful string manipulation tools you have at your disposal.

到目前为止,你已经使用了很多字符串,但没有学习太多细节。现在是时候深入研究它们,了解字符串的工作原理,并掌握一些你可以使用的强大字符串操作工具了。

We’ll begin with the details of creating strings and character vectors. You’ll then dive into creating strings from data, then the opposite: extracting strings from data. We’ll then discuss tools that work with individual letters. The chapter finishes with functions that work with individual letters and a brief discussion of where your expectations from English might steer you wrong when working with other languages.

我们将从创建字符串和字符向量的细节开始。然后你将深入学习如何从数据创建字符串,以及反过来:从数据中提取字符串。接着我们将讨论处理单个字母的工具。本章最后会介绍处理单个字母的函数,并简要讨论在处理其他语言时,你基于英语的预期可能会如何误导你。

We’ll keep working with strings in the next chapter, where you’ll learn more about the power of regular expressions.

在下一章中,我们将继续学习字符串,届时你将了解更多关于正则表达式 (regular expressions) 的强大功能。

14.1.1 Prerequisites

In this chapter, we’ll use functions from the stringr package, which is part of the core tidyverse. We’ll also use the babynames data since it provides some fun strings to manipulate.

在本章中,我们将使用 stringr 包中的函数,它是核心 tidyverse 的一部分。我们还将使用 babynames 数据,因为它提供了一些有趣的字符串可供操作。

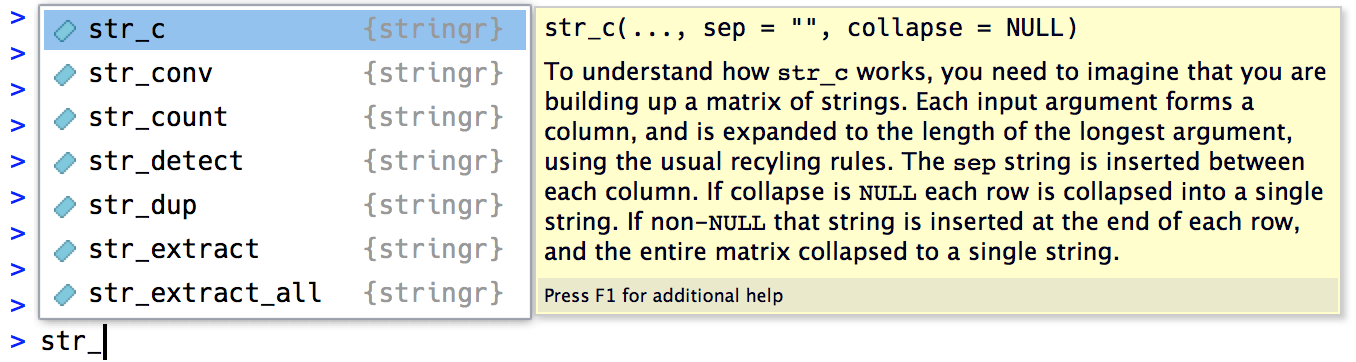

You can quickly tell when you’re using a stringr function because all stringr functions start with str_. This is particularly useful if you use RStudio because typing str_ will trigger autocomplete, allowing you to jog your memory of the available functions.

你可以很快判断出你正在使用的是 stringr 函数,因为所有的 stringr 函数都以 str_ 开头。如果你使用 RStudio,这一点特别有用,因为输入 str_ 会触发自动补全,从而帮助你记起可用的函数。

14.2 Creating a string

We’ve created strings in passing earlier in the book but didn’t discuss the details. Firstly, you can create a string using either single quotes (') or double quotes ("). There’s no difference in behavior between the two, so in the interests of consistency, the tidyverse style guide recommends using ", unless the string contains multiple ".

在本书前面部分,我们不经意间创建了字符串,但没有讨论细节。首先,你可以使用单引号 (') 或双引号 (") 来创建字符串。两者在行为上没有区别,因此为了保持一致性,tidyverse 风格指南 建议使用 ",除非字符串本身包含多个 "。

string1 <- "This is a string"

string2 <- 'If I want to include a "quote" inside a string, I use single quotes'If you forget to close a quote, you’ll see +, the continuation prompt:

如果你忘记关闭引号,你会看到 +,即续行提示符:

> "This is a string without a closing quote

+

+

+ HELP I'M STUCK IN A STRINGIf this happens to you and you can’t figure out which quote to close, press Escape to cancel and try again.

如果你遇到这种情况,并且不知道该关闭哪个引号,请按 Escape 键取消并重试。

14.2.1 Escapes

To include a literal single or double quote in a string, you can use \ to “escape” it:

要在字符串中包含字面上的单引号或双引号,你可以使用 \ 来“转义”它:

double_quote <- "\"" # or '"'

single_quote <- '\'' # or "'"So if you want to include a literal backslash in your string, you’ll need to escape it: "\\":

因此,如果你想在字符串中包含一个字面上的反斜杠,你需要对它进行转义:"\\":

backslash <- "\\"Beware that the printed representation of a string is not the same as the string itself because the printed representation shows the escapes (in other words, when you print a string, you can copy and paste the output to recreate that string). To see the raw contents of the string, use str_view()1:

注意,字符串的打印表示形式与字符串本身并不相同,因为打印表示形式会显示转义字符(换句话说,当你打印一个字符串时,你可以复制并粘贴输出来重新创建该字符串)。要查看字符串的原始内容,请使用 str_view()1:

14.2.2 Raw strings

Creating a string with multiple quotes or backslashes gets confusing quickly. To illustrate the problem, let’s create a string that contains the contents of the code block where we define the double_quote and single_quote variables:

创建一个包含多个引号或反斜杠的字符串很快就会变得混乱。为了说明这个问题,让我们创建一个字符串,它包含我们定义 double_quote 和 single_quote 变量的代码块的内容:

tricky <- "double_quote <- \"\\\"\" # or '\"'

single_quote <- '\\'' # or \"'\""

str_view(tricky)

#> [1] │ double_quote <- "\"" # or '"'

#> │ single_quote <- '\'' # or "'"That’s a lot of backslashes! (This is sometimes called leaning toothpick syndrome.) To eliminate the escaping, you can instead use a raw string2:

这里有太多的反斜杠了!(这有时被称为“斜杠牙签综合症” (leaning toothpick syndrome))。为了消除转义,你可以改用原始字符串 (raw string)2:

tricky <- r"(double_quote <- "\"" # or '"'

single_quote <- '\'' # or "'")"

str_view(tricky)

#> [1] │ double_quote <- "\"" # or '"'

#> │ single_quote <- '\'' # or "'"A raw string usually starts with r"( and finishes with )". But if your string contains )" you can instead use r"[]" or r"{}", and if that’s still not enough, you can insert any number of dashes to make the opening and closing pairs unique, e.g., r"--()--", r"---()---", etc. Raw strings are flexible enough to handle any text.

原始字符串通常以 r"( 开始,以 )" 结束。但是,如果你的字符串包含 )",你可以改用 r"[]" 或 r"{}",如果这还不够,你可以插入任意数量的破折号来使开始和结束对唯一,例如 r"--()--"、r"---()---" 等。原始字符串足够灵活,可以处理任何文本。

14.2.3 Other special characters

As well as \", \', and \\, there are a handful of other special characters that may come in handy. The most common are \n, a new line, and \t, tab. You’ll also sometimes see strings containing Unicode escapes that start with \u or \U. This is a way of writing non-English characters that work on all systems. You can see the complete list of other special characters in ?Quotes.

除了 \"、\' 和 \\,还有一些其他可能派上用场的特殊字符。最常见的是 \n(换行符)和 \t(制表符)。你有时也会看到包含以 \u 或 \U 开头的 Unicode 转义序列的字符串。这是一种在所有系统上都能正常工作的非英文字符的书写方式。你可以在 ?Quotes 中看到其他特殊字符的完整列表。

Note that str_view() uses curly braces for tabs to make them easier to spot3. One of the challenges of working with text is that there’s a variety of ways that white space can end up in the text, so this background helps you recognize that something strange is going on.

请注意 str_view() 对制表符使用花括号,以便更容易发现它们3。处理文本的挑战之一是,空白字符 (white space) 可能以多种方式出现在文本中,所以这个背景知识可以帮助你识别出是否发生了异常情况。

14.2.4 Exercises

-

Create strings that contain the following values:

He said "That's amazing!"\a\b\c\d\\\\\\

-

Create the string in your R session and print it. What happens to the special “\u00a0”? How does

str_view()display it? Can you do a little googling to figure out what this special character is?{r} x <- "This\u00a0is\u00a0tricky"

14.3 Creating many strings from data

Now that you’ve learned the basics of creating a string or two by “hand”, we’ll go into the details of creating strings from other strings. This will help you solve the common problem where you have some text you wrote that you want to combine with strings from a data frame. For example, you might combine “Hello” with a name variable to create a greeting. We’ll show you how to do this with str_c() and str_glue() and how you can use them with mutate(). That naturally raises the question of what stringr functions you might use with summarize(), so we’ll finish this section with a discussion of str_flatten(), which is a summary function for strings.

现在你已经学会了如何“手动”创建一两个字符串的基础知识,接下来我们将深入探讨如何从其他字符串创建字符串。这将帮助你解决一个常见问题:你有一些自己编写的文本,并希望将其与数据框中的字符串结合起来。例如,你可能想将 “Hello” 与一个 name 变量结合起来创建一个问候语。我们将向你展示如何使用 str_c() 和 str_glue() 来实现这一点,以及如何将它们与 mutate() 一起使用。这自然引出了一个问题:你可以将哪些 stringr 函数与 summarize() 一起使用?因此,本节最后将讨论 str_flatten(),这是一个用于字符串的汇总函数。

14.3.1 str_c()

str_c() takes any number of vectors as arguments and returns a character vector:str_c() 接受任意数量的向量作为参数,并返回一个字符向量:

str_c() is very similar to the base paste0(), but is designed to be used with mutate() by obeying the usual tidyverse rules for recycling and propagating missing values:str_c() 与基础函数 paste0() 非常相似,但它遵循 tidyverse 通常的回收规则和缺失值传播规则,因此被设计为与 mutate() 一起使用:

If you want missing values to display in another way, use coalesce() to replace them. Depending on what you want, you might use it either inside or outside of str_c():

如果你想让缺失值以其他方式显示,可以使用 coalesce() 来替换它们。根据你的需求,你可以在 str_c() 内部或外部使用它:

df |>

mutate(

greeting1 = str_c("Hi ", coalesce(name, "you"), "!"),

greeting2 = coalesce(str_c("Hi ", name, "!"), "Hi!")

)

#> # A tibble: 4 × 3

#> name greeting1 greeting2

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 Flora Hi Flora! Hi Flora!

#> 2 David Hi David! Hi David!

#> 3 Terra Hi Terra! Hi Terra!

#> 4 <NA> Hi you! Hi!

14.3.2 str_glue()

If you are mixing many fixed and variable strings with str_c(), you’ll notice that you type a lot of "s, making it hard to see the overall goal of the code. An alternative approach is provided by the glue package via str_glue()4. You give it a single string that has a special feature: anything inside {} will be evaluated like it’s outside of the quotes:

如果你使用 str_c() 混合许多固定的和可变的字符串,你会发现你输入了大量的 ",这使得代码的整体目标难以看清。glue 包通过 str_glue()4 提供了另一种方法。你给它一个具有特殊功能的单一字符串:在 {} 内的任何内容都会像在引号之外一样被求值:

As you can see, str_glue() currently converts missing values to the string "NA", unfortunately making it inconsistent with str_c().

正如你所见,str_glue() 目前将缺失值转换为字符串 "NA",不幸的是,这使其与 str_c() 不一致。

You also might wonder what happens if you need to include a regular { or } in your string. You’re on the right track if you guess you’ll need to escape it somehow. The trick is that glue uses a slightly different escaping technique: instead of prefixing with special character like \, you double up the special characters:

你可能还会想,如果需要在字符串中包含常规的 { 或 },会发生什么。如果你猜到需要以某种方式转义它,那你就猜对了。诀窍是 glue 使用一种稍有不同的转义技术:不是像 \ 那样使用特殊字符作为前缀,而是将特殊字符加倍:

14.3.3 str_flatten()

str_c() and str_glue() work well with mutate() because their output is the same length as their inputs. What if you want a function that works well with summarize(), i.e. something that always returns a single string? That’s the job of str_flatten()5: it takes a character vector and combines each element of the vector into a single string:str_c() 和 str_glue() 与 mutate() 配合得很好,因为它们的输出长度与输入长度相同。如果你想要一个能与 summarize() 很好地配合使用的函数,即一个总是返回单个字符串的函数,该怎么办?这就是 str_flatten()5 的工作:它接受一个字符向量,并将向量的每个元素合并成一个单一的字符串:

str_flatten(c("x", "y", "z"))

#> [1] "xyz"

str_flatten(c("x", "y", "z"), ", ")

#> [1] "x, y, z"

str_flatten(c("x", "y", "z"), ", ", last = ", and ")

#> [1] "x, y, and z"This makes it work well with summarize():

这使得它能与 summarize() 很好地配合使用:

df <- tribble(

~ name, ~ fruit,

"Carmen", "banana",

"Carmen", "apple",

"Marvin", "nectarine",

"Terence", "cantaloupe",

"Terence", "papaya",

"Terence", "mandarin"

)

df |>

group_by(name) |>

summarize(fruits = str_flatten(fruit, ", "))

#> # A tibble: 3 × 2

#> name fruits

#> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 Carmen banana, apple

#> 2 Marvin nectarine

#> 3 Terence cantaloupe, papaya, mandarin14.3.4 Exercises

-

Compare and contrast the results of

paste0()withstr_c()for the following inputs: What’s the difference between

paste()andpaste0()? How can you recreate the equivalent ofpaste()withstr_c()?-

Convert the following expressions from

str_c()tostr_glue()or vice versa:str_c("The price of ", food, " is ", price)str_glue("I'm {age} years old and live in {country}")str_c("\\section{", title, "}")

14.4 Extracting data from strings

It’s very common for multiple variables to be crammed together into a single string. In this section, you’ll learn how to use four tidyr functions to extract them:

将多个变量塞进一个字符串里是非常常见的。在本节中,你将学习如何使用四个 tidyr 函数来提取它们:

df |> separate_longer_delim(col, delim)df |> separate_longer_position(col, width)df |> separate_wider_delim(col, delim, names)df |> separate_wider_position(col, widths)

If you look closely, you can see there’s a common pattern here: separate_, then longer or wider, then _, then by delim or position. That’s because these four functions are composed of two simpler primitives:

如果你仔细观察,你会发现这里有一个共同的模式:separate_,然后是 longer 或 wider,然后是 _,再然后是 delim 或 position。这是因为这四个函数是由两个更简单的原语组成的:

Just like with

pivot_longer()andpivot_wider(),_longerfunctions make the input data frame longer by creating new rows and_widerfunctions make the input data frame wider by generating new columns.

就像pivot_longer()和pivot_wider()一样,_longer函数通过创建新行来使输入数据框变长,而_wider函数通过生成新列来使输入数据框变宽。delimsplits up a string with a delimiter like", "or" ";positionsplits at specified widths, likec(3, 5, 2).delim使用像", "或" "这样的分隔符 (delimiter) 来分割字符串;position则在指定的宽度处进行分割,例如c(3, 5, 2)。

We’ll return to the last member of this family, separate_wider_regex(), in Chapter 15. It’s the most flexible of the wider functions, but you need to know something about regular expressions before you can use it.

我们将在 Chapter 15 中回到这个家族的最后一个成员 separate_wider_regex()。它是 wider 函数中最灵活的一个,但在使用它之前,你需要对正则表达式有所了解。

The following two sections will give you the basic idea behind these separate functions, first separating into rows (which is a little simpler) and then separating into columns. We’ll finish off by discussing the tools that the wider functions give you to diagnose problems.

接下来的两节将为你介绍这些 separate 函数背后的基本思想,首先是分拆到行(这稍微简单一些),然后是分拆到列。最后,我们将讨论 wider 函数提供的用于诊断问题的工具。

14.4.1 Separating into rows

Separating a string into rows tends to be most useful when the number of components varies from row to row. The most common case is requiring separate_longer_delim() to split based on a delimiter:

当组件数量因行而异时,将字符串分拆到行通常最有用。最常见的情况是需要 separate_longer_delim() 基于分隔符进行分割:

df1 <- tibble(x = c("a,b,c", "d,e", "f"))

df1 |>

separate_longer_delim(x, delim = ",")

#> # A tibble: 6 × 1

#> x

#> <chr>

#> 1 a

#> 2 b

#> 3 c

#> 4 d

#> 5 e

#> 6 fIt’s rarer to see separate_longer_position() in the wild, but some older datasets do use a very compact format where each character is used to record a value:

在实际应用中很少见到 separate_longer_position(),但一些较旧的数据集确实会使用一种非常紧凑的格式,其中每个字符都用于记录一个值:

df2 <- tibble(x = c("1211", "131", "21"))

df2 |>

separate_longer_position(x, width = 1)

#> # A tibble: 9 × 1

#> x

#> <chr>

#> 1 1

#> 2 2

#> 3 1

#> 4 1

#> 5 1

#> 6 3

#> # ℹ 3 more rows14.4.2 Separating into columns

Separating a string into columns tends to be most useful when there are a fixed number of components in each string, and you want to spread them into columns. They are slightly more complicated than their longer equivalents because you need to name the columns. For example, in this following dataset, x is made up of a code, an edition number, and a year, separated by ".". To use separate_wider_delim(), we supply the delimiter and the names in two arguments:

当每个字符串中都有固定数量的组件,并且你想将它们分散到列中时,将字符串分拆到列通常最有用。它们比 longer 对应的函数稍微复杂一些,因为你需要为列命名。例如,在下面的数据集中,x 由一个代码、一个版本号和一个年份组成,用 "." 分隔。要使用 separate_wider_delim(),我们在两个参数中提供分隔符和名称:

df3 <- tibble(x = c("a10.1.2022", "b10.2.2011", "e15.1.2015"))

df3 |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = ".",

names = c("code", "edition", "year")

)

#> # A tibble: 3 × 3

#> code edition year

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 a10 1 2022

#> 2 b10 2 2011

#> 3 e15 1 2015If a specific piece is not useful you can use an NA name to omit it from the results:

如果某个特定的部分没有用,你可以使用 NA 名称将其从结果中省略:

df3 |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = ".",

names = c("code", NA, "year")

)

#> # A tibble: 3 × 2

#> code year

#> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 a10 2022

#> 2 b10 2011

#> 3 e15 2015separate_wider_position() works a little differently because you typically want to specify the width of each column. So you give it a named integer vector, where the name gives the name of the new column, and the value is the number of characters it occupies. You can omit values from the output by not naming them:separate_wider_position() 的工作方式稍有不同,因为你通常需要指定每列的宽度。因此,你需要给它一个命名的整数向量,其中名称给出新列的名称,值是它占用的字符数。你可以通过不命名来从输出中省略值:

df4 <- tibble(x = c("202215TX", "202122LA", "202325CA"))

df4 |>

separate_wider_position(

x,

widths = c(year = 4, age = 2, state = 2)

)

#> # A tibble: 3 × 3

#> year age state

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 2022 15 TX

#> 2 2021 22 LA

#> 3 2023 25 CA14.4.3 Diagnosing widening problems

separate_wider_delim()6 requires a fixed and known set of columns. What happens if some of the rows don’t have the expected number of pieces? There are two possible problems, too few or too many pieces, so separate_wider_delim() provides two arguments to help: too_few and too_many. Let’s first look at the too_few case with the following sample dataset:separate_wider_delim()6 需要一个固定且已知的列集合。如果某些行没有预期的片段数量会发生什么?可能存在两种问题,片段太少或太多,因此 separate_wider_delim() 提供了两个参数来帮助解决:too_few 和 too_many。让我们首先用以下示例数据集看一下 too_few 的情况:

df <- tibble(x = c("1-1-1", "1-1-2", "1-3", "1-3-2", "1"))

df |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = "-",

names = c("x", "y", "z")

)

#> Error in `separate_wider_delim()`:

#> ! Expected 3 pieces in each element of `x`.

#> ! 2 values were too short.

#> ℹ Use `too_few = "debug"` to diagnose the problem.

#> ℹ Use `too_few = "align_start"/"align_end"` to silence this message.You’ll notice that we get an error, but the error gives us some suggestions on how you might proceed. Let’s start by debugging the problem:

你会注意到我们收到了一个错误,但这个错误为我们提供了一些关于如何继续操作的建议。让我们从调试问题开始:

debug <- df |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = "-",

names = c("x", "y", "z"),

too_few = "debug"

)

#> Warning: Debug mode activated: adding variables `x_ok`, `x_pieces`, and

#> `x_remainder`.

debug

#> # A tibble: 5 × 6

#> x y z x_ok x_pieces x_remainder

#> <chr> <chr> <chr> <lgl> <int> <chr>

#> 1 1-1-1 1 1 TRUE 3 ""

#> 2 1-1-2 1 2 TRUE 3 ""

#> 3 1-3 3 <NA> FALSE 2 ""

#> 4 1-3-2 3 2 TRUE 3 ""

#> 5 1 <NA> <NA> FALSE 1 ""When you use the debug mode, you get three extra columns added to the output: x_ok, x_pieces, and x_remainder (if you separate a variable with a different name, you’ll get a different prefix). Here, x_ok lets you quickly find the inputs that failed:

当你使用调试模式时,输出中会添加三个额外的列:x_ok、x_pieces 和 x_remainder(如果你分割一个不同名称的变量,你会得到一个不同的前缀)。在这里,x_ok 可以让你快速找到失败的输入:

debug |> filter(!x_ok)

#> # A tibble: 2 × 6

#> x y z x_ok x_pieces x_remainder

#> <chr> <chr> <chr> <lgl> <int> <chr>

#> 1 1-3 3 <NA> FALSE 2 ""

#> 2 1 <NA> <NA> FALSE 1 ""x_pieces tells us how many pieces were found, compared to the expected 3 (the length of names). x_remainder isn’t useful when there are too few pieces, but we’ll see it again shortly.x_pieces 告诉我们找到了多少个片段,与预期的 3 个(names 的长度)相比。当片段太少时,x_remainder 没有用,但我们很快会再次看到它。

Sometimes looking at this debugging information will reveal a problem with your delimiter strategy or suggest that you need to do more preprocessing before separating. In that case, fix the problem upstream and make sure to remove too_few = "debug" to ensure that new problems become errors.

有时查看这些调试信息会揭示你的分隔符策略存在问题,或者建议你在分割之前需要进行更多的预处理。在这种情况下,请修复上游的问题,并确保删除 too_few = "debug" 以确保新问题会成为错误。

In other cases, you may want to fill in the missing pieces with NAs and move on. That’s the job of too_few = "align_start" and too_few = "align_end" which allow you to control where the NAs should go:

在其他情况下,你可能希望用 NA 填充缺失的片段然后继续。这是 too_few = "align_start" 和 too_few = "align_end" 的工作,它们允许你控制 NA 应该放在哪里:

df |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = "-",

names = c("x", "y", "z"),

too_few = "align_start"

)

#> # A tibble: 5 × 3

#> x y z

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 1 1 1

#> 2 1 1 2

#> 3 1 3 <NA>

#> 4 1 3 2

#> 5 1 <NA> <NA>The same principles apply if you have too many pieces:

如果你有太多片段,同样的原则也适用:

df <- tibble(x = c("1-1-1", "1-1-2", "1-3-5-6", "1-3-2", "1-3-5-7-9"))

df |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = "-",

names = c("x", "y", "z")

)

#> Error in `separate_wider_delim()`:

#> ! Expected 3 pieces in each element of `x`.

#> ! 2 values were too long.

#> ℹ Use `too_many = "debug"` to diagnose the problem.

#> ℹ Use `too_many = "drop"/"merge"` to silence this message.But now, when we debug the result, you can see the purpose of x_remainder:

但是现在,当我们调试结果时,你可以看到 x_remainder 的用途:

debug <- df |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = "-",

names = c("x", "y", "z"),

too_many = "debug"

)

#> Warning: Debug mode activated: adding variables `x_ok`, `x_pieces`, and

#> `x_remainder`.

debug |> filter(!x_ok)

#> # A tibble: 2 × 6

#> x y z x_ok x_pieces x_remainder

#> <chr> <chr> <chr> <lgl> <int> <chr>

#> 1 1-3-5-6 3 5 FALSE 4 -6

#> 2 1-3-5-7-9 3 5 FALSE 5 -7-9You have a slightly different set of options for handling too many pieces: you can either silently “drop” any additional pieces or “merge” them all into the final column:

对于处理过多片段,你有一套稍微不同的选项:你可以默默地“丢弃”(drop) 任何额外的片段,或者将它们全部“合并”(merge) 到最后一列:

df |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = "-",

names = c("x", "y", "z"),

too_many = "drop"

)

#> # A tibble: 5 × 3

#> x y z

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 1 1 1

#> 2 1 1 2

#> 3 1 3 5

#> 4 1 3 2

#> 5 1 3 5

df |>

separate_wider_delim(

x,

delim = "-",

names = c("x", "y", "z"),

too_many = "merge"

)

#> # A tibble: 5 × 3

#> x y z

#> <chr> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 1 1 1

#> 2 1 1 2

#> 3 1 3 5-6

#> 4 1 3 2

#> 5 1 3 5-7-914.5 Letters

In this section, we’ll introduce you to functions that allow you to work with the individual letters within a string. You’ll learn how to find the length of a string, extract substrings, and handle long strings in plots and tables.

在本节中,我们将向你介绍一些可以处理字符串中单个字母的函数。你将学习如何查找字符串的长度、提取子字符串以及在图表和表格中处理长字符串。

14.5.1 Length

str_length() tells you the number of letters in the string:str_length() 会告诉你字符串中的字母数量:

str_length(c("a", "R for data science", NA))

#> [1] 1 18 NAYou could use this with count() to find the distribution of lengths of US babynames and then with filter() to look at the longest names, which happen to have 15 letters7:

你可以将其与 count() 一起使用,以查找美国婴儿名字长度的分布,然后与 filter() 一起使用,以查看最长的名字,这些名字恰好有 15 个字母7:

babynames |>

count(length = str_length(name), wt = n)

#> # A tibble: 14 × 2

#> length n

#> <int> <int>

#> 1 2 338150

#> 2 3 8589596

#> 3 4 48506739

#> 4 5 87011607

#> 5 6 90749404

#> 6 7 72120767

#> # ℹ 8 more rows

babynames |>

filter(str_length(name) == 15) |>

count(name, wt = n, sort = TRUE)

#> # A tibble: 34 × 2

#> name n

#> <chr> <int>

#> 1 Franciscojavier 123

#> 2 Christopherjohn 118

#> 3 Johnchristopher 118

#> 4 Christopherjame 108

#> 5 Christophermich 52

#> 6 Ryanchristopher 45

#> # ℹ 28 more rows14.5.2 Subsetting

You can extract parts of a string using str_sub(string, start, end), where start and end are the positions where the substring should start and end. The start and end arguments are inclusive, so the length of the returned string will be end - start + 1:

你可以使用 str_sub(string, start, end) 来提取字符串的一部分,其中 start 和 end 是子字符串应该开始和结束的位置。start 和 end 参数是包含性的,所以返回的字符串长度将是 end - start + 1:

You can use negative values to count back from the end of the string: -1 is the last character, -2 is the second to last character, etc.

你可以使用负值从字符串末尾向后计数:-1 是最后一个字符,-2 是倒数第二个字符,依此类推。

str_sub(x, -3, -1)

#> [1] "ple" "ana" "ear"Note that str_sub() won’t fail if the string is too short: it will just return as much as possible:

请注意,如果字符串太短,str_sub() 不会失败:它只会尽可能多地返回内容:

str_sub("a", 1, 5)

#> [1] "a"We could use str_sub() with mutate() to find the first and last letter of each name:

我们可以将 str_sub() 与 mutate() 结合使用,找出每个名字的首字母和尾字母:

babynames |>

mutate(

first = str_sub(name, 1, 1),

last = str_sub(name, -1, -1)

)

#> # A tibble: 1,924,665 × 7

#> year sex name n prop first last

#> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <int> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 1880 F Mary 7065 0.0724 M y

#> 2 1880 F Anna 2604 0.0267 A a

#> 3 1880 F Emma 2003 0.0205 E a

#> 4 1880 F Elizabeth 1939 0.0199 E h

#> 5 1880 F Minnie 1746 0.0179 M e

#> 6 1880 F Margaret 1578 0.0162 M t

#> # ℹ 1,924,659 more rows14.5.3 Exercises

- When computing the distribution of the length of babynames, why did we use

wt = n?

- Use

str_length()andstr_sub()to extract the middle letter from each baby name. What will you do if the string has an even number of characters?

- Are there any major trends in the length of babynames over time? What about the popularity of first and last letters?

14.6 Non-English text

So far, we’ve focused on English language text which is particularly easy to work with for two reasons. Firstly, the English alphabet is relatively simple: there are just 26 letters. Secondly (and maybe more importantly), the computing infrastructure we use today was predominantly designed by English speakers. Unfortunately, we don’t have room for a full treatment of non-English languages. Still, we wanted to draw your attention to some of the biggest challenges you might encounter: encoding, letter variations, and locale-dependent functions.

到目前为止,我们一直专注于英文文本,这种文本特别容易处理,原因有二。首先,英文字母相对简单:只有 26 个字母。其次(也许更重要的是),我们今天使用的计算基础设施主要是由英语使用者设计的。不幸的是,我们没有足够的篇幅来全面处理非英语语言。不过,我们想提醒你注意一些你可能遇到的最大挑战:编码 (encoding)、字母变体和依赖于区域设置 (locale-dependent) 的函数。

14.6.1 Encoding

When working with non-English text, the first challenge is often the encoding. To understand what’s going on, we need to dive into how computers represent strings. In R, we can get at the underlying representation of a string using charToRaw():

在处理非英文文本时,第一个挑战通常是编码 (encoding)。要理解发生了什么,我们需要深入了解计算机如何表示字符串。在 R 中,我们可以使用 charToRaw() 来获取字符串的底层表示:

charToRaw("Hadley")

#> [1] 48 61 64 6c 65 79Each of these six hexadecimal numbers represents one letter: 48 is H, 61 is a, and so on. The mapping from hexadecimal number to character is called the encoding, and in this case, the encoding is called ASCII. ASCII does a great job of representing English characters because it’s the American Standard Code for Information Interchange.

这六个十六进制数中的每一个都代表一个字母:48 是 H,61 是 a,依此类推。从十六进制数到字符的映射称为编码,在这种情况下,编码被称为 ASCII。ASCII 在表示英文字符方面做得很好,因为它是美国信息交换标准代码。

Things aren’t so easy for languages other than English. In the early days of computing, there were many competing standards for encoding non-English characters. For example, there were two different encodings for Europe: Latin1 (aka ISO-8859-1) was used for Western European languages, and Latin2 (aka ISO-8859-2) was used for Central European languages. In Latin1, the byte b1 is “±”, but in Latin2, it’s “ą”! Fortunately, today there is one standard that is supported almost everywhere: UTF-8. UTF-8 can encode just about every character used by humans today and many extra symbols like emojis.

对于非英语语言来说,事情就没那么简单了。在计算的早期,有许多竞争性的标准用于编码非英文字符。例如,欧洲有两种不同的编码:Latin1(又名 ISO-8859-1)用于西欧语言,而 Latin2(又名 ISO-8859-2)用于中欧语言。在 Latin1 中,字节 b1 是 “±”,但在 Latin2 中,它是 “ą”!幸运的是,如今有一个几乎在任何地方都得到支持的标准:UTF-8。UTF-8 几乎可以编码当今人类使用的所有字符以及许多额外的符号,如表情符号 (emojis)。

readr uses UTF-8 everywhere. This is a good default but will fail for data produced by older systems that don’t use UTF-8. If this happens, your strings will look weird when you print them. Sometimes just one or two characters might be messed up; other times, you’ll get complete gibberish. For example here are two inline CSVs with unusual encodings8:

readr 在任何地方都使用 UTF-8。这是一个很好的默认设置,但对于由不使用 UTF-8 的旧系统生成的数据,它会失败。如果发生这种情况,你的字符串在打印时会看起来很奇怪。有时可能只有一两个字符被弄乱;其他时候,你会得到完全的乱码。例如,这里有两个带有不寻常编码的内联 CSV8:

To read these correctly, you specify the encoding via the locale argument:

要正确读取这些文件,你需要通过 locale 参数指定编码:

How do you find the correct encoding? If you’re lucky, it’ll be included somewhere in the data documentation. Unfortunately, that’s rarely the case, so readr provides guess_encoding() to help you figure it out. It’s not foolproof and works better when you have lots of text (unlike here), but it’s a reasonable place to start. Expect to try a few different encodings before you find the right one.

你如何找到正确的编码?如果幸运的话,它会包含在数据文档的某个地方。不幸的是,这种情况很少见,所以 readr 提供了 guess_encoding() 来帮助你确定它。它并非万无一失,并且在你拥有大量文本时效果更好(不像这里),但它是一个合理的起点。预计你需要尝试几种不同的编码才能找到正确的那一个。

Encodings are a rich and complex topic; we’ve only scratched the surface here. If you’d like to learn more, we recommend reading the detailed explanation at http://kunststube.net/encoding/.

编码是一个内容丰富且复杂的主题;我们在这里只是浅尝辄止。如果你想了解更多,我们建议阅读 http://kunststube.net/encoding/ 上的详细解释。

14.6.2 Letter variations

Working in languages with accents poses a significant challenge when determining the position of letters (e.g., with str_length() and str_sub()) as accented letters might be encoded as a single individual character (e.g., ü) or as two characters by combining an unaccented letter (e.g., u) with a diacritic mark (e.g., ¨). For example, this code shows two ways of representing ü that look identical:

在处理带重音符号的语言时,确定字母的位置(例如,使用 str_length() 和 str_sub())会带来重大挑战,因为带重音的字母可能被编码为单个独立字符(例如,ü),或者通过组合一个不带重音的字母(例如,u)和一个变音符号(例如,¨)而被编码为两个字符。例如,这段代码显示了两种看起来完全相同的表示 ü 的方式:

But both strings differ in length, and their first characters are different:

但这两个字符串的长度不同,它们的第一个字符也不同:

str_length(u)

#> [1] 1 2

str_sub(u, 1, 1)

#> [1] "ü" "u"Finally, note that a comparison of these strings with == interprets these strings as different, while the handy str_equal() function in stringr recognizes that both have the same appearance:

最后,请注意,使用 == 比较这些字符串会将其解释为不同的字符串,而 stringr 中方便的 str_equal() 函数则能识别出两者具有相同的外观:

u[[1]] == u[[2]]

#> [1] FALSE

str_equal(u[[1]], u[[2]])

#> [1] TRUE14.6.3 Locale-dependent functions

Finally, there are a handful of stringr functions whose behavior depends on your locale. A locale is similar to a language but includes an optional region specifier to handle regional variations within a language. A locale is specified by a lower-case language abbreviation, optionally followed by a _ and an upper-case region identifier. For example, “en” is English, “en_GB” is British English, and “en_US” is American English. If you don’t already know the code for your language, Wikipedia has a good list, and you can see which are supported in stringr by looking at stringi::stri_locale_list().

最后,还有一些 stringr 函数的行为取决于你的区域设置 (locale)。locale 类似于一种语言,但包含一个可选的区域说明符,以处理一种语言内部的区域差异。locale 由小写语言缩写指定,后面可选择性地跟一个 _ 和一个大写的区域标识符。例如,“en” 是英语,“en_GB” 是英式英语,“en_US” 是美式英语。如果你还不知道你语言的代码,维基百科 有一个很好的列表,你也可以通过查看 stringi::stri_locale_list() 来看 stringr 支持哪些。

Base R string functions automatically use the locale set by your operating system. This means that base R string functions do what you expect for your language, but your code might work differently if you share it with someone who lives in a different country. To avoid this problem, stringr defaults to English rules by using the “en” locale and requires you to specify the locale argument to override it. Fortunately, there are only two sets of functions where the locale really matters: changing case and sorting.

基础 R 字符串函数会自动使用你的操作系统设置的 locale。这意味着基础 R 字符串函数会按照你语言的预期工作,但如果你的代码与生活在不同国家的人共享,它的工作方式可能会有所不同。为避免此问题,stringr 默认使用 “en” locale,即英语规则,并要求你指定 locale 参数来覆盖它。幸运的是,只有两组函数的 locale 真正重要:改变大小写和排序。

The rules for changing cases differ among languages. For example, Turkish has two i’s: with and without a dot. Since they’re two distinct letters, they’re capitalized differently:

不同语言的大小写转换规则不同。例如,土耳其语中有两个 i:带点的和不带点的。由于它们是两个不同的字母,它们的大写方式也不同:

str_to_upper(c("i", "ı"))

#> [1] "I" "I"

str_to_upper(c("i", "ı"), locale = "tr")

#> [1] "İ" "I"Sorting strings depends on the order of the alphabet, and the order of the alphabet is not the same in every language9! Here’s an example: in Czech, “ch” is a compound letter that appears after h in the alphabet.

字符串排序取决于字母表的顺序,而并非每种语言的字母表顺序都相同9!这里有一个例子:在捷克语中,“ch” 是一个复合字母,在字母表中出现在 h 之后。

This also comes up when sorting strings with dplyr::arrange(), which is why it also has a locale argument.

在使用 dplyr::arrange() 对字符串进行排序时也会遇到这种情况,这就是为什么它也有一个 locale 参数。

14.7 Summary

In this chapter, you’ve learned about some of the power of the stringr package: how to create, combine, and extract strings, and about some of the challenges you might face with non-English strings. Now it’s time to learn one of the most important and powerful tools for working with strings: regular expressions. Regular expressions are a very concise but very expressive language for describing patterns within strings and are the topic of the next chapter.

在本章中,你学习了 stringr 包的一些强大功能:如何创建、组合和提取字符串,以及在处理非英语字符串时可能面临的一些挑战。现在是时候学习处理字符串最重要和最强大的工具之一:正则表达式。正则表达式是一种非常简洁但表达能力极强的语言,用于描述字符串内的模式,这也是下一章的主题。

Or use the base R function

writeLines().↩︎Available in R 4.0.0 and above.↩︎

str_view()also uses color to bring tabs, spaces, matches, etc. to your attention. The colors don’t currently show up in the book, but you’ll notice them when running code interactively.↩︎If you’re not using stringr, you can also access it directly with

glue::glue().↩︎The base R equivalent is

paste()used with thecollapseargument.↩︎The same principles apply to

separate_wider_position()andseparate_wider_regex().↩︎Looking at these entries, we’d guess that the babynames data drops spaces or hyphens and truncates after 15 letters.↩︎

Here I’m using the special

\xto encode binary data directly into a string.↩︎Sorting in languages that don’t have an alphabet, like Chinese, is more complicated still.↩︎