Introduction

Data science is an exciting discipline that allows you to transform raw data into understanding, insight, and knowledge. The goal of “R for Data Science” is to help you learn the most important tools in R that will allow you to do data science efficiently and reproducibly, and to have some fun along the way 😃. After reading this book, you’ll have the tools to tackle a wide variety of data science challenges using the best parts of R.

数据科学是一门激动人心的学科,它能让你将原始数据转化为理解、洞见和知识。 《R 数据科学》的目标是帮助你学习 R 中最重要的工具,让你能够高效、可复现地进行数据科学工作,并在此过程中获得一些乐趣 😃。 读完本书后,你将拥有使用 R 的精华部分来应对各种数据科学挑战的工具。

What you will learn

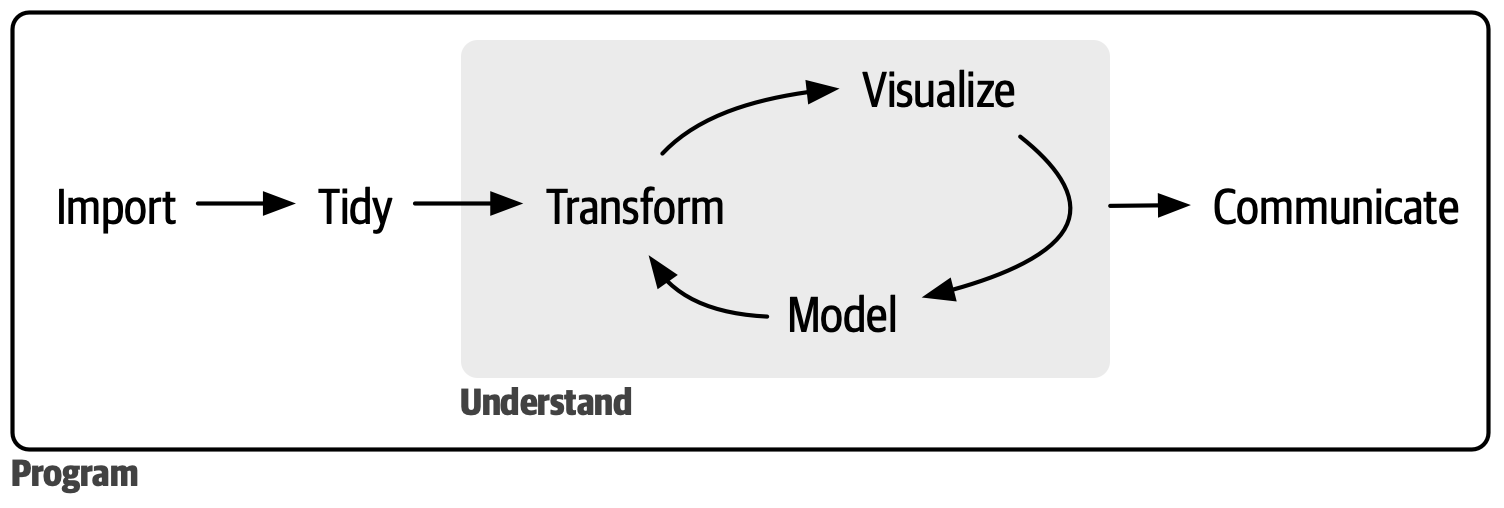

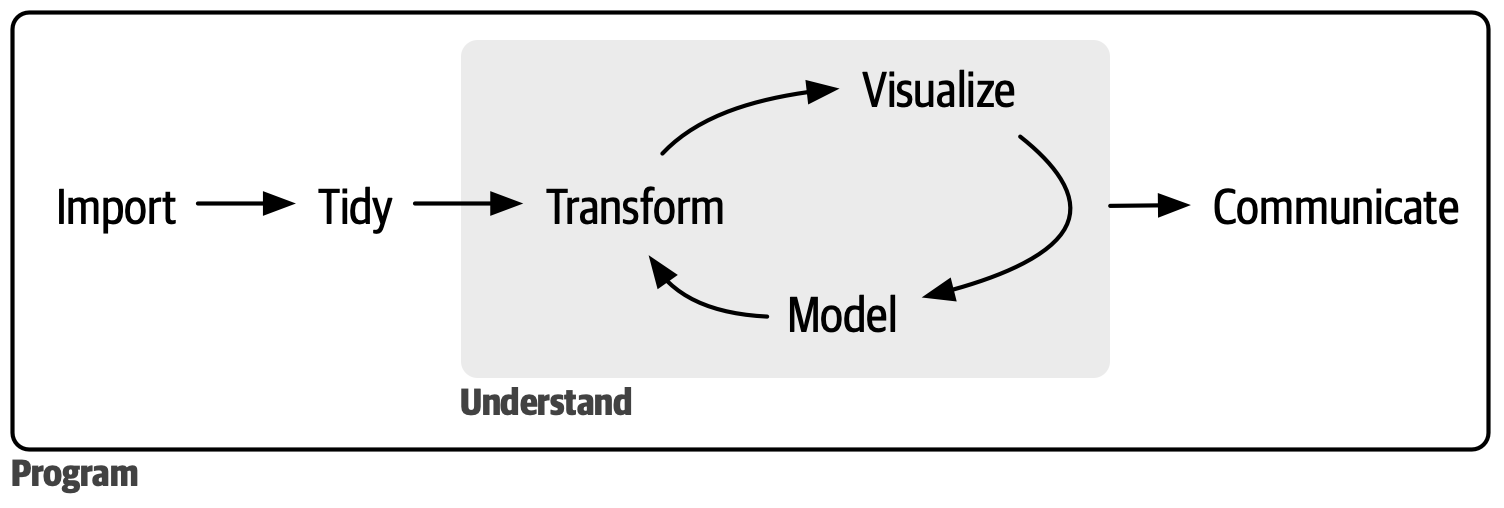

Data science is a vast field, and there’s no way you can master it all by reading a single book. This book aims to give you a solid foundation in the most important tools and enough knowledge to find the resources to learn more when necessary. Our model of the steps of a typical data science project looks something like Figure 1.

数据科学是一个广阔的领域,不可能通过阅读一本书就掌握所有内容。 本书旨在为你打下最重要的工具的坚实基础,并提供足够的知识,以便你在必要时能找到资源进行更深入的学习。 我们对一个典型数据科学项目步骤的模型如 Figure 1 所示。

First, you must import your data into R. This typically means that you take data stored in a file, database, or web application programming interface (API) and load it into a data frame in R. If you can’t get your data into R, you can’t do data science on it!

首先,你必须将数据 导入 (import) R 中。 这通常意味着你将存储在文件、数据库或网络应用程序编程接口 (API) 中的数据加载到 R 的数据框中。 如果你不能将数据导入 R,你就无法对其进行数据科学分析!

Once you’ve imported your data, it is a good idea to tidy it. Tidying your data means storing it in a consistent form that matches the semantics of the dataset with how it is stored. In brief, when your data is tidy, each column is a variable and each row is an observation. Tidy data is important because the consistent structure lets you focus your efforts on answering questions about the data, not fighting to get the data into the right form for different functions.

导入数据后,最好对其进行 整理 (tidy)。 整理数据意味着以一种一致的形式存储数据,使其存储方式与数据集的语义相匹配。 简而言之,当你的数据是整洁的,每一列都是一个变量,每一行都是一个观测。 整洁的数据很重要,因为一致的结构让你能集中精力回答关于数据的问题,而不是费力地将数据转换成不同函数所需的正确形式。

Once you have tidy data, a common next step is to transform it. Transformation includes narrowing in on observations of interest (like all people in one city or all data from the last year), creating new variables that are functions of existing variables (like computing speed from distance and time), and calculating a set of summary statistics (like counts or means). Together, tidying and transforming are called wrangling because getting your data in a form that’s natural to work with often feels like a fight!

一旦你有了整洁的数据,通常的下一步是进行 转换 (transform)。 转换包括筛选感兴趣的观测值(例如某个城市的所有人或去年的所有数据),根据现有变量创建新变量(例如根据距离和时间计算速度),以及计算一组汇总统计数据(例如计数或均值)。 整理和转换一起被称为 数据整理 (wrangling),因为将数据处理成便于使用的形式通常感觉像一场战斗!

Once you have tidy data with the variables you need, there are two main engines of knowledge generation: visualization and modeling. These have complementary strengths and weaknesses, so any real data analysis will iterate between them many times.

一旦你获得了包含所需变量的整洁数据,便有两种主要的知识生成引擎:可视化和建模。 这两者各有优缺点,互为补充,因此任何实际的数据分析都会在它们之间多次迭代。

Visualization is a fundamentally human activity. A good visualization will show you things you did not expect or raise new questions about the data. A good visualization might also hint that you’re asking the wrong question or that you need to collect different data. Visualizations can surprise you, but they don’t scale particularly well because they require a human to interpret them.

可视化 (Visualization) 本质上是一项人类活动。 好的可视化会向你展示意想不到的事情,或引发关于数据的新问题。 好的可视化也可能暗示你问错了问题,或者你需要收集不同的数据。 可视化可以给你带来惊喜,但它们的可扩展性不是特别好,因为它们需要人来解释。

Models are complementary tools to visualization. Once you have made your questions sufficiently precise, you can use a model to answer them. Models are fundamentally mathematical or computational tools, so they generally scale well. Even when they don’t, it’s usually cheaper to buy more computers than it is to buy more brains! But every model makes assumptions, and by its very nature, a model cannot question its own assumptions. That means a model cannot fundamentally surprise you.

模型 (Models) 是可视化的补充工具。 一旦你的问题足够精确,你就可以使用模型来回答它们。 模型本质上是数学或计算工具,所以它们通常具有良好的可扩展性。 即使它们不具备,购买更多的计算机通常也比购买更多的人脑便宜! 但是每个模型都有其假设,而模型本质上无法质疑自身的假设。 这意味着模型根本上无法给你带来惊喜。

The last step of data science is communication, an absolutely critical part of any data analysis project. It doesn’t matter how well your models and visualization have led you to understand the data unless you can also communicate your results to others.

数据科学的最后一步是 沟通 (communication),这是任何数据分析项目中至关重要的一部分。 无论你的模型和可视化让你对数据理解得有多透彻,除非你也能将你的结果传达给他人,否则一切都是徒劳。

Surrounding all these tools is programming. Programming is a cross-cutting tool that you use in nearly every part of a data science project. You don’t need to be an expert programmer to be a successful data scientist, but learning more about programming pays off because becoming a better programmer allows you to automate common tasks and solve new problems with greater ease.

围绕所有这些工具的是 编程 (programming)。 编程是一项贯穿始终的工具,你在数据科学项目的几乎每个环节都会用到它。 你不需要成为一名专家程序员才能成为一名成功的数据科学家,但学习更多关于编程的知识是值得的,因为成为一个更好的程序员可以让你自动化处理常见任务,并更轻松地解决新问题。

You’ll use these tools in every data science project, but they’re not enough for most projects. There’s a rough 80/20 rule at play: you can tackle about 80% of every project using the tools you’ll learn in this book, but you’ll need other tools to tackle the remaining 20%. Throughout this book, we’ll point you to resources where you can learn more.

你将在每个数据科学项目中使用这些工具,但对大多数项目来说,它们还不够。 这里有一个大致的 80/20 法则:你可以使用本书中学到的工具处理每个项目中大约 80% 的工作,但你需要其他工具来处理剩下的 20%。 在本书中,我们会为你指出可以学习更多知识的资源。

How this book is organized

The previous description of the tools of data science is organized roughly according to the order in which you use them in an analysis (although, of course, you’ll iterate through them multiple times). In our experience, however, learning data importing and tidying first is suboptimal because, 80% of the time, it’s routine and boring, and the other 20% of the time, it’s weird and frustrating. That’s a bad place to start learning a new subject! Instead, we’ll start with visualization and transformation of data that’s already been imported and tidied. That way, when you ingest and tidy your own data, your motivation will stay high because you know the pain is worth the effort.

前文对数据科学工具的描述大致是按照你在分析中使用的顺序来组织的(当然,你会多次迭代使用它们)。 然而,根据我们的经验,首先学习数据导入和整理并非最佳选择,因为 80% 的时间这项工作是常规且乏味的,而另外 20% 的时间则是古怪且令人沮丧的。 这对于开始学习一个新主题来说是个糟糕的起点! 因此,我们将从已经导入和整理好的数据的可视化和转换开始。 这样,当你处理和整理自己的数据时,你的动力会保持高昂,因为你知道这些辛苦是值得的。

Within each chapter, we try to adhere to a consistent pattern: start with some motivating examples so you can see the bigger picture, and then dive into the details. Each section of the book is paired with exercises to help you practice what you’ve learned. Although it can be tempting to skip the exercises, there’s no better way to learn than by practicing on real problems.

在每一章中,我们都力求遵循一种一致的模式:从一些激励性的例子开始,让你看到全局,然后深入细节。 书中的每一节都配有练习,以帮助你实践所学。 虽然跳过练习很诱人,但没有比通过解决实际问题更好的学习方法了。

What you won’t learn

There are several important topics that this book doesn’t cover. We believe it’s important to stay ruthlessly focused on the essentials so you can get up and running as quickly as possible. That means this book can’t cover every important topic.

本书未涵盖一些重要主题。 我们认为,严格专注于核心内容,以便你能尽快上手,这一点至关重要。 这意味着本书无法涵盖所有重要主题。

Modeling

Modeling is super important for data science, but it’s a big topic, and unfortunately, we just don’t have the space to give it the coverage it deserves here. To learn more about modeling, we highly recommend Tidy Modeling with R by our colleagues Max Kuhn and Julia Silge. This book will teach you the tidymodels family of packages, which, as you might guess from the name, share many conventions with the tidyverse packages we use in this book.

建模对于数据科学超级重要,但它是一个很大的主题,不幸的是,我们在这里没有足够的篇幅给予它应有的介绍。 要学习更多关于建模的知识,我们强烈推荐我们的同事 Max Kuhn 和 Julia Silge 编写的 《Tidy Modeling with R》。 这本书将教你 tidymodels 系列的包,正如你可能从名字中猜到的那样,它们与我们在本书中使用的 tidyverse 包有许多共同的约定。

Big data

This book proudly and primarily focuses on small, in-memory datasets. This is the right place to start because you can’t tackle big data unless you have experience with small data. The tools you’ll learn throughout the majority of this book will easily handle hundreds of megabytes of data, and with a bit of care, you can typically use them to work with a few gigabytes of data. We’ll also show you how to get data out of databases and parquet files, both of which are often used to store big data. You won’t necessarily be able to work with the entire dataset, but that’s not a problem because you only need a subset or subsample to answer the question that you’re interested in.

本书主要且自豪地专注于小型的、内存中的数据集。 这是一个正确的起点,因为除非你有处理小数据的经验,否则你无法处理大数据。 你在本书大部分章节中学到的工具可以轻松处理数百兆字节的数据,稍加注意,你通常可以用它们来处理几千兆字节的数据。 我们还将向你展示如何从数据库和 parquet 文件中获取数据,这两种文件都常用于存储大数据。 你不一定能够处理整个数据集,但这不成问题,因为你只需要一个子集或子样本来回答你感兴趣的问题。

If you’re routinely working with larger data (10–100 GB, say), we recommend learning more about data.table. We don’t teach it here because it uses a different interface than the tidyverse and requires you to learn some different conventions. However, it is incredibly faster, and the performance payoff is worth investing some time in learning it if you’re working with large data.

如果你经常处理更大数据(比如 10-100 GB),我们建议你学习更多关于 data.table 的知识。 我们在这里不教它,因为它使用了与 tidyverse 不同的接口,需要你学习一些不同的约定。 然而,它的速度快得惊人,如果你处理的是大数据,为了性能提升而花时间学习它是值得的。

Python, Julia, and friends

In this book, you won’t learn anything about Python, Julia, or any other programming language useful for data science. This isn’t because we think these tools are bad. They’re not! And in practice, most data science teams use a mix of languages, often at least R and Python. But we strongly believe that it’s best to master one tool at a time, and R is a great place to start.

在本书中,你不会学到任何关于 Python、Julia 或其他用于数据科学的编程语言的知识。 这并非因为我们认为这些工具不好。 它们很好! 在实践中,大多数数据科学团队会混合使用多种语言,通常至少包括 R 和 Python。 但我们坚信,最好一次只掌握一种工具,而 R 是一个很好的起点。

Prerequisites

We’ve made a few assumptions about what you already know to get the most out of this book. You should be generally numerically literate, and it’s helpful if you have some basic programming experience already. If you’ve never programmed before, you might find Hands on Programming with R by Garrett to be a valuable adjunct to this book.

为了让你能从本书中获得最大收益,我们对你已有的知识做了一些假设。 你应该具备基本的数学素养,如果已经有一些基础的编程经验会很有帮助。 如果你以前从未编程过,你可能会发现 Garrett 编写的 《Hands on Programming with R》 是本书的一个有价值的补充。

You need four things to run the code in this book: R, RStudio, a collection of R packages called the tidyverse, and a handful of other packages. Packages are the fundamental units of reproducible R code. They include reusable functions, documentation that describes how to use them, and sample data.

要运行本书中的代码,你需要四样东西:R、RStudio、一个名为 tidyverse 的 R 包集合,以及其他几个包。 包是可复现 R 代码的基本单位。 它们包含可重用的函数、描述如何使用它们的文档以及示例数据。

R

To download R, go to CRAN, the comprehensive R archive network, https://cloud.r-project.org. A new major version of R comes out once a year, and there are 2-3 minor releases each year. It’s a good idea to update regularly. Upgrading can be a bit of a hassle, especially for major versions that require you to re-install all your packages, but putting it off only makes it worse. We recommend R 4.2.0 or later for this book.

要下载 R,请访问 CRAN(comprehensive R archive network,综合 R 存档网络),网址为 https://cloud.r-project.org。 R 每年发布一个新的主版本,每年还有 2-3 个次要版本发布。 定期更新是个好主意。 升级可能有点麻烦,特别是主版本升级需要你重新安装所有包,但拖延只会让事情变得更糟。 我们推荐为本书使用 R 4.2.0 或更高版本。

RStudio

RStudio is an integrated development environment, or IDE, for R programming, which you can download from https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/. RStudio is updated a couple of times a year, and it will automatically let you know when a new version is out, so there’s no need to check back. It’s a good idea to upgrade regularly to take advantage of the latest and greatest features. For this book, make sure you have at least RStudio 2022.02.0.

RStudio 是 R 编程的集成开发环境(IDE),你可以从 https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/ 下载。 RStudio 每年更新几次,当有新版本发布时,它会自动通知你,所以无需反复检查。 定期升级以利用最新最强大的功能是个好主意。 对于本书,请确保你至少安装了 RStudio 2022.02.0 版本。

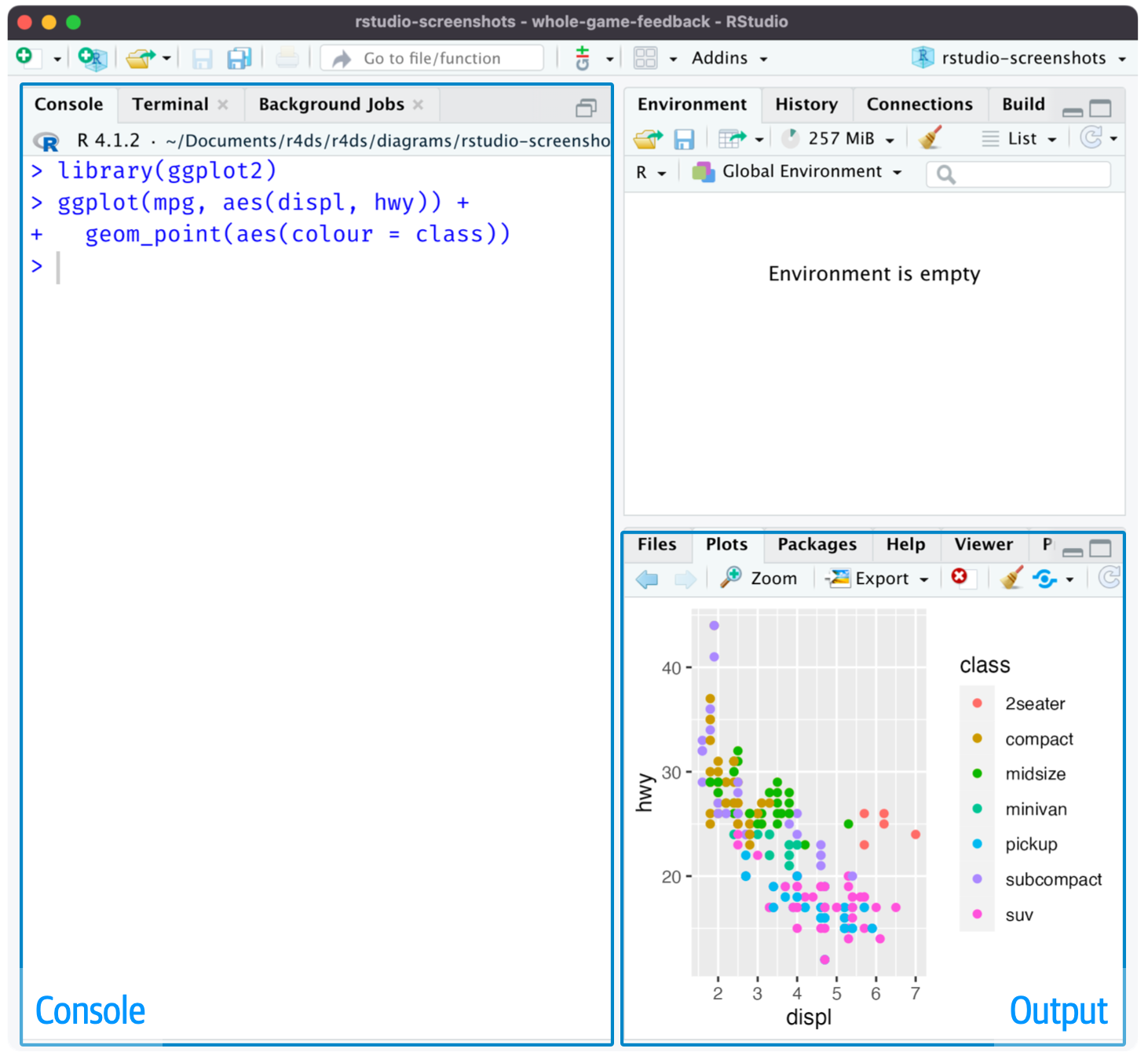

When you start RStudio, Figure 2, you’ll see two key regions in the interface: the console pane and the output pane. For now, all you need to know is that you type the R code in the console pane and press enter to run it. You’ll learn more as we go along!1

当你启动 RStudio 时(见 Figure 2),你会在界面中看到两个关键区域:控制台窗格和输出窗格。 目前,你只需要知道,在控制台窗格中输入 R 代码,然后按 Enter 键来运行它。 随着学习的深入,你会了解更多!1

The tidyverse

You’ll also need to install some R packages. An R package is a collection of functions, data, and documentation that extends the capabilities of base R. Using packages is key to the successful use of R. The majority of the packages that you will learn in this book are part of the so-called tidyverse. All packages in the tidyverse share a common philosophy of data and R programming and are designed to work together.

你还需要安装一些 R 包。 R 包 (package) 是一个集函数、数据和文档于一体的集合,它扩展了基础 R 的功能。 使用包是成功使用 R 的关键。 你将在本书中学到的大部分包都属于所谓的 tidyverse。 tidyverse 中的所有包都共享一套关于数据和 R 编程的共同理念,并且被设计为可以协同工作。

You can install the complete tidyverse with a single line of code:

你可以用一行代码安装完整的 tidyverse:

install.packages("tidyverse")On your computer, type that line of code in the console, and then press enter to run it. R will download the packages from CRAN and install them on your computer.

在你的电脑上,在控制台中输入那行代码,然后按回车键运行它。 R 将从 CRAN 下载这些包并安装到你的电脑上。

You will not be able to use the functions, objects, or help files in a package until you load it with library(). Once you have installed a package, you can load it using the library() function:

在你使用 library() 加载一个包之前,你将无法使用该包中的函数、对象或帮助文件。 一旦安装了包,你可以使用 library() 函数来加载它:

library(tidyverse)

#> ── Attaching core tidyverse packages ───────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

#> ✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

#> ✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

#> ✔ ggplot2 3.5.2 ✔ tibble 3.3.0

#> ✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

#> ✔ purrr 1.0.4

#> ── Conflicts ─────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

#> ✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

#> ✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

#> ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorsThis tells you that tidyverse loads nine packages: dplyr, forcats, ggplot2, lubridate, purrr, readr, stringr, tibble, tidyr. These are considered the core of the tidyverse because you’ll use them in almost every analysis.

这会告诉你 tidyverse 加载了九个包:dplyr、forcats、ggplot2、lubridate、purrr、readr、stringr、tibble 和 tidyr。 这些被认为是 tidyverse 的 核心 (core),因为你几乎在每次分析中都会用到它们。

Packages in the tidyverse change fairly frequently. You can see if updates are available by running tidyverse_update().

tidyverse 中的包更新相当频繁。 你可以通过运行 tidyverse_update() 来查看是否有可用的更新。

Other packages

There are many other excellent packages that are not part of the tidyverse because they solve problems in a different domain or are designed with a different set of underlying principles. This doesn’t make them better or worse; it just makes them different. In other words, the complement to the tidyverse is not the messyverse but many other universes of interrelated packages. As you tackle more data science projects with R, you’ll learn new packages and new ways of thinking about data.

还有许多其他优秀的包不属于 tidyverse,因为它们解决的是不同领域的问题,或者遵循不同的底层设计原则。 这并不能说它们更好或更差,只是它们不同。 换句话说,tidyverse 的补充不是 messyverse (混乱宇宙),而是许多其他相互关联的包的宇宙。 随着你用 R 攻克更多的数据科学项目,你将学到新的包和新的数据思维方式。

We’ll use many packages from outside the tidyverse in this book. For example, we’ll use the following packages because they provide interesting datasets for us to work with in the process of learning R:

在本书中,我们将使用许多来自 tidyverse 之外的包。 例如,我们将使用以下包,因为它们在我们学习 R 的过程中提供了有趣的数据集供我们使用:

install.packages(

c("arrow", "babynames", "curl", "duckdb", "gapminder",

"ggrepel", "ggridges", "ggthemes", "hexbin", "janitor", "Lahman",

"leaflet", "maps", "nycflights13", "openxlsx", "palmerpenguins",

"repurrrsive", "tidymodels", "writexl")

)We’ll also use a selection of other packages for one off examples. You don’t need to install them now, just remember that whenever you see an error like this:

我们还将为一些一次性的例子使用其他一些包。 你现在不需要安装它们,只需记住,当你看到如下错误时:

You need to run install.packages("ggrepel") to install the package.

你需要运行 install.packages("ggrepel") 来安装这个包。

Running R code

The previous section showed you several examples of running R code. The code in the book looks like this:

上一节向你展示了几个运行 R 代码的例子。 书中的代码看起来是这样的:

1 + 2

#> [1] 3If you run the same code in your local console, it will look like this:

如果你在本地控制台运行同样的代码,它会看起来是这样的:

> 1 + 2

[1] 3There are two main differences. In your console, you type after the >, called the prompt; we don’t show the prompt in the book. In the book, the output is commented out with #>; in your console, it appears directly after your code. These two differences mean that if you’re working with an electronic version of the book, you can easily copy code out of the book and paste it into the console.

这里有两个主要区别。 在你的控制台里,你在 >(称为 提示符 (prompt))后面输入;我们在书中不显示提示符。 在书中,输出被 #> 注释掉了;在你的控制台里,它直接出现在你的代码后面。 这两个区别意味着,如果你正在使用本书的电子版,你可以很容易地从书中复制代码并粘贴到控制台。

Throughout the book, we use a consistent set of conventions to refer to code:

在整本书中,我们使用一套一致的约定来引用代码:

- Functions are displayed in a code font and followed by parentheses, like sum() or mean().

函数会以代码字体显示,并后跟括号,如 sum() 或 mean()。

- Other R objects (such as data or function arguments) are in a code font, without parentheses, like flights or x.

其他的 R 对象(比如数据或函数参数)会以代码字体显示,不带括号,如 flights 或 x。

- Sometimes, to make it clear which package an object comes from, we’ll use the package name followed by two colons, like dplyr::mutate() or nycflights13::flights. This is also valid R code.

有时,为了明确一个对象来自哪个包,我们会使用包名后跟两个冒号的形式,比如 dplyr::mutate() 或 nycflights13::flights。 这也是有效的 R 代码。

Acknowledgments

This book isn’t just the product of Hadley, Mine, and Garrett but is the result of many conversations (in person and online) that we’ve had with many people in the R community. We’re incredibly grateful for all the conversations we’ve had with y’all; thank you so much!

这本书不仅仅是 Hadley、Mine 和 Garrett 的成果,也是我们与 R 社区中许多人进行多次对话(线上和线下)的结晶。 我们非常感谢与各位进行的所有对话;非常感谢你们!

This book was written in the open, and many people contributed via pull requests. A special thanks to all 259 of you who contributed improvements via GitHub pull requests (in alphabetical order by username): @a-rosenberg, Tim Becker (@a2800276), Abinash Satapathy (@Abinashbunty), Adam Gruer (@adam-gruer), adi pradhan (@adidoit), A. s. (@Adrianzo), Aep Hidyatuloh (@aephidayatuloh), Andrea Gilardi (@agila5), Ajay Deonarine (@ajay-d), @AlanFeder, Daihe Sui (@alansuidaihe), @alberto-agudo, @AlbertRapp, @aleloi, pete (@alonzi), Alex (@ALShum), Andrew M. (@amacfarland), Andrew Landgraf (@andland), @andyhuynh92, Angela Li (@angela-li), Antti Rask (@AnttiRask), LOU Xun (@aquarhead), @ariespirgel, @august-18, Michael Henry (@aviast), Azza Ahmed (@azzaea), Steven Moran (@bambooforest), Brian G. Barkley (@BarkleyBG), Mara Averick (@batpigandme), Oluwafemi OYEDELE (@BB1464), Brent Brewington (@bbrewington), Bill Behrman (@behrman), Ben Herbertson (@benherbertson), Ben Marwick (@benmarwick), Ben Steinberg (@bensteinberg), Benjamin Yeh (@bentyeh), Betul Turkoglu (@betulturkoglu), Brandon Greenwell (@bgreenwell), Bianca Peterson (@BinxiePeterson), Birger Niklas (@BirgerNi), Brett Klamer (@bklamer), @boardtc, Christian (@c-hoh), Caddy (@caddycarine), Camille V Leonard (@camillevleonard), @canovasjm, Cedric Batailler (@cedricbatailler), Christina Wei (@christina-wei), Christian Mongeau (@chrMongeau), Cooper Morris (@coopermor), Colin Gillespie (@csgillespie), Rademeyer Vermaak (@csrvermaak), Chloe Thierstein (@cthierst), Chris Saunders (@ctsa), Abhinav Singh (@curious-abhinav), Curtis Alexander (@curtisalexander), Christian G. Warden (@cwarden), Charlotte Wickham (@cwickham), Kenny Darrell (@darrkj), David Kane (@davidkane9), David (@davidrsch), David Rubinger (@davidrubinger), David Clark (@DDClark), Derwin McGeary (@derwinmcgeary), Daniel Gromer (@dgromer), @Divider85, @djbirke, Danielle Navarro (@djnavarro), Russell Shean (@DOH-RPS1303), Zhuoer Dong (@dongzhuoer), Devin Pastoor (@dpastoor), @DSGeoff, Devarshi Thakkar (@dthakkar09), Julian During (@duju211), Dylan Cashman (@dylancashman), Dirk Eddelbuettel (@eddelbuettel), Edwin Thoen (@EdwinTh), Ahmed El-Gabbas (@elgabbas), Henry Webel (@enryH), Ercan Karadas (@ercan7), Eric Kitaif (@EricKit), Eric Watt (@ericwatt), Erik Erhardt (@erikerhardt), Etienne B. Racine (@etiennebr), Everett Robinson (@evjrob), @fellennert, Flemming Miguel (@flemmingmiguel), Floris Vanderhaeghe (@florisvdh), @funkybluehen, @gabrivera, Garrick Aden-Buie (@gadenbuie), Peter Ganong (@ganong123), Gerome Meyer (@GeroVanMi), Gleb Ebert (@gl-eb), Josh Goldberg (@GoldbergData), bahadir cankardes (@gridgrad), Gustav W Delius (@gustavdelius), Hao Chen (@hao-trivago), Harris McGehee (@harrismcgehee), @hendrikweisser, Hengni Cai (@hengnicai), Iain (@Iain-S), Ian Sealy (@iansealy), Ian Lyttle (@ijlyttle), Ivan Krukov (@ivan-krukov), Jacob Kaplan (@jacobkap), Jazz Weisman (@jazzlw), John Blischak (@jdblischak), John D. Storey (@jdstorey), Gregory Jefferis (@jefferis), Jeffrey Stevens (@JeffreyRStevens), 蒋雨蒙 (@JeldorPKU), Jennifer (Jenny) Bryan (@jennybc), Jen Ren (@jenren), Jeroen Janssens (@jeroenjanssens), @jeromecholewa, Janet Wesner (@jilmun), Jim Hester (@jimhester), JJ Chen (@jjchern), Jacek Kolacz (@jkolacz), Joanne Jang (@joannejang), @johannes4998, John Sears (@johnsears), @jonathanflint, Jon Calder (@jonmcalder), Jonathan Page (@jonpage), Jon Harmon (@jonthegeek), JooYoung Seo (@jooyoungseo), Justinas Petuchovas (@jpetuchovas), Jordan (@jrdnbradford), Jeffrey Arnold (@jrnold), Jose Roberto Ayala Solares (@jroberayalas), Joyce Robbins (@jtr13), @juandering, Julia Stewart Lowndes (@jules32), Sonja (@kaetschap), Kara Woo (@karawoo), Katrin Leinweber (@katrinleinweber), Karandeep Singh (@kdpsingh), Kevin Perese (@kevinxperese), Kevin Ferris (@kferris10), Kirill Sevastyanenko (@kirillseva), Jonathan Kitt (@KittJonathan), @koalabearski, Kirill Müller (@krlmlr), Rafał Kucharski (@kucharsky), Kevin Wright (@kwstat), Noah Landesberg (@landesbergn), Lawrence Wu (@lawwu), @lindbrook, Luke W Johnston (@lwjohnst86), Kara de la Marck (@MarckK), Kunal Marwaha (@marwahaha), Matan Hakim (@matanhakim), Matthias Liew (@MatthiasLiew), Matt Wittbrodt (@MattWittbrodt), Mauro Lepore (@maurolepore), Mark Beveridge (@mbeveridge), @mcewenkhundi, mcsnowface, PhD (@mcsnowface), Matt Herman (@mfherman), Michael Boerman (@michaelboerman), Mitsuo Shiota (@mitsuoxv), Matthew Hendrickson (@mjhendrickson), @MJMarshall, Misty Knight-Finley (@mkfin7), Mohammed Hamdy (@mmhamdy), Maxim Nazarov (@mnazarov), Maria Paula Caldas (@mpaulacaldas), Mustafa Ascha (@mustafaascha), Nelson Areal (@nareal), Nate Olson (@nate-d-olson), Nathanael (@nateaff), @nattalides, Ned Western (@NedJWestern), Nick Clark (@nickclark1000), @nickelas, Nirmal Patel (@nirmalpatel), Nischal Shrestha (@nischalshrestha), Nicholas Tierney (@njtierney), Jakub Nowosad (@Nowosad), Nick Pullen (@nstjhp), @olivier6088, Olivier Cailloux (@oliviercailloux), Robin Penfold (@p0bs), Pablo E. Garcia (@pabloedug), Paul Adamson (@padamson), Penelope Y (@penelopeysm), Peter Hurford (@peterhurford), Peter Baumgartner (@petzi53), Patrick Kennedy (@pkq), Pooya Taherkhani (@pooyataher), Y. Yu (@PursuitOfDataScience), Radu Grosu (@radugrosu), Ranae Dietzel (@Ranae), Ralph Straumann (@rastrau), Rayna M Harris (@raynamharris), @ReeceGoding, Robin Gertenbach (@rgertenbach), Jajo (@RIngyao), Riva Quiroga (@rivaquiroga), Richard Knight (@RJHKnight), Richard Zijdeman (@rlzijdeman), @robertchu03, Robin Kohrs (@RobinKohrs), Robin (@Robinlovelace), Emily Robinson (@robinsones), Rob Tenorio (@robtenorio), Rod Mazloomi (@RodAli), Rohan Alexander (@RohanAlexander), Romero Morais (@RomeroBarata), Albert Y. Kim (@rudeboybert), Saghir (@saghirb), Hojjat Salmasian (@salmasian), Jonas (@sauercrowd), Vebash Naidoo (@sciencificity), Seamus McKinsey (@seamus-mckinsey), @seanpwilliams, Luke Smith (@seasmith), Matthew Sedaghatfar (@sedaghatfar), Sebastian Kraus (@sekR4), Sam Firke (@sfirke), Shannon Ellis (@ShanEllis), @shoili, Christian Heinrich (@Shurakai), S’busiso Mkhondwane (@sibusiso16), SM Raiyyan (@sm-raiyyan), Jakob Krigovsky (@sonicdoe), Stephan Koenig (@stephan-koenig), Stephen Balogun (@stephenbalogun), Steven M. Mortimer (@StevenMMortimer), Stéphane Guillou (@stragu), Sulgi Kim (@sulgik), Sergiusz Bleja (@svenski), Tal Galili (@talgalili), Alec Fisher (@Taurenamo), Todd Gerarden (@tgerarden), Tom Godfrey (@thomasggodfrey), Tim Broderick (@timbroderick), Tim Waterhouse (@timwaterhouse), TJ Mahr (@tjmahr), Thomas Klebel (@tklebel), Tom Prior (@tomjamesprior), Terence Teo (@tteo), @twgardner2, Ulrik Lyngs (@ulyngs), Shinya Uryu (@uribo), Martin Van der Linden (@vanderlindenma), Walter Somerville (@waltersom), @werkstattcodes, Will Beasley (@wibeasley), Yihui Xie (@yihui), Yiming (Paul) Li (@yimingli), @yingxingwu, Hiroaki Yutani (@yutannihilation), Yu Yu Aung (@yuyu-aung), Zach Bogart (@zachbogart), @zeal626, Zeki Akyol (@zekiakyol).

Colophon

An online version of this book is available at https://r4ds.hadley.nz. It will continue to evolve in between reprints of the physical book. The source of the book is available at https://github.com/hadley/r4ds. The book is powered by Quarto, which makes it easy to write books that combine text and executable code.

本书的在线版本可在 https://r4ds.hadley.nz 查看。 在实体书再版之间,它会不断演进。 本书的源代码可在 https://github.com/hadley/r4ds 找到。 本书由 Quarto 驱动,它使得编写结合文本和可执行代码的书籍变得容易。

If you’d like a comprehensive overview of all of RStudio’s features, see the RStudio User Guide at https://docs.posit.co/ide/user.↩︎