12 Logical vectors

12.1 Introduction

In this chapter, you’ll learn tools for working with logical vectors. Logical vectors are the simplest type of vector because each element can only be one of three possible values: TRUE, FALSE, and NA. It’s relatively rare to find logical vectors in your raw data, but you’ll create and manipulate them in the course of almost every analysis.

在本章中,你将学习使用逻辑向量的工具。逻辑向量是最简单的向量类型,因为每个元素只能是三个可能值之一:TRUE、FALSE 和 NA。在原始数据中相对较少见到逻辑向量,但你几乎在每一次分析过程中都会创建和操作它们。

We’ll begin by discussing the most common way of creating logical vectors: with numeric comparisons. Then you’ll learn about how you can use Boolean algebra to combine different logical vectors, as well as some useful summaries. We’ll finish off with if_else() and case_when(), two useful functions for making conditional changes powered by logical vectors.

我们将从讨论创建逻辑向量最常见的方法开始:使用数值比较。然后,你将学习如何使用布尔代数来组合不同的逻辑向量,以及一些有用的汇总方法。最后,我们将介绍 if_else() 和 case_when(),这是两个由逻辑向量驱动、用于进行条件性变更的有用函数。

12.1.1 Prerequisites

Most of the functions you’ll learn about in this chapter are provided by base R, so we don’t need the tidyverse, but we’ll still load it so we can use mutate(), filter(), and friends to work with data frames. We’ll also continue to draw examples from the nycflights13::flights dataset.

本章你将学到的大多数函数都由 R base 提供,所以我们不需要 tidyverse,但我们仍然会加载它,以便我们可以使用 mutate()、filter() 及其他相关函数来处理数据框。我们也将继续使用 nycflights13::flights 数据集中的例子。

However, as we start to cover more tools, there won’t always be a perfect real example. So we’ll start making up some dummy data with c():

然而,随着我们开始介绍更多的工具,并不总能找到一个完美的真实案例。因此,我们将开始使用 c() 创建一些虚拟数据:

x <- c(1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13)

x * 2

#> [1] 2 4 6 10 14 22 26This makes it easier to explain individual functions at the cost of making it harder to see how it might apply to your data problems. Just remember that any manipulation we do to a free-floating vector, you can do to a variable inside a data frame with mutate() and friends.

这样做虽然更容易解释单个函数,但代价是更难看出它如何应用于你的数据问题。只需记住,我们对一个独立向量所做的任何操作,你都可以通过 mutate() 及相关函数对数据框内的变量进行同样的操作。

12.2 Comparisons

A very common way to create a logical vector is via a numeric comparison with <, <=, >, >=, !=, and ==. So far, we’ve mostly created logical variables transiently within filter() — they are computed, used, and then thrown away. For example, the following filter finds all daytime departures that arrive roughly on time:

创建逻辑向量的一个非常常见的方法是通过数值比较,使用 <, <=, >, >=, !=, 和 ==。到目前为止,我们主要是在 filter() 中临时创建逻辑变量——它们被计算、使用,然后被丢弃。例如,下面的筛选器可以找出所有在白天出发且大致准时到达的航班:

flights |>

filter(dep_time > 600 & dep_time < 2000 & abs(arr_delay) < 20)

#> # A tibble: 172,286 × 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 601 600 1 844 850

#> 2 2013 1 1 602 610 -8 812 820

#> 3 2013 1 1 602 605 -3 821 805

#> 4 2013 1 1 606 610 -4 858 910

#> 5 2013 1 1 606 610 -4 837 845

#> 6 2013 1 1 607 607 0 858 915

#> # ℹ 172,280 more rows

#> # ℹ 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>, carrier <chr>, flight <int>, …It’s useful to know that this is a shortcut and you can explicitly create the underlying logical variables with mutate():

了解这是一种快捷方式会很有用,你也可以使用 mutate() 显式地创建底层的逻辑变量:

flights |>

mutate(

daytime = dep_time > 600 & dep_time < 2000,

approx_ontime = abs(arr_delay) < 20,

.keep = "used"

)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 × 4

#> dep_time arr_delay daytime approx_ontime

#> <int> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl>

#> 1 517 11 FALSE TRUE

#> 2 533 20 FALSE FALSE

#> 3 542 33 FALSE FALSE

#> 4 544 -18 FALSE TRUE

#> 5 554 -25 FALSE FALSE

#> 6 554 12 FALSE TRUE

#> # ℹ 336,770 more rowsThis is particularly useful for more complicated logic because naming the intermediate steps makes it easier to both read your code and check that each step has been computed correctly.

这对于更复杂的逻辑尤其有用,因为为中间步骤命名可以使你的代码更易于阅读,也更容易检查每一步是否计算正确。

All up, the initial filter is equivalent to:

总而言之,最初的筛选器等同于:

12.2.1 Floating point comparison

Beware of using == with numbers. For example, it looks like this vector contains the numbers 1 and 2:

注意,当处理数字时要小心使用 ==。例如,下面这个向量看起来包含了数字 1 和 2:

But if you test them for equality, you get FALSE:

但如果你测试它们是否相等,你会得到 FALSE:

x == c(1, 2)

#> [1] FALSE FALSEWhat’s going on? Computers store numbers with a fixed number of decimal places so there’s no way to exactly represent 1/49 or sqrt(2) and subsequent computations will be very slightly off. We can see the exact values by calling print() with the digits1 argument:

这是怎么回事?计算机以固定的小数位数存储数字,因此无法精确表示 1/49 或 sqrt(2),后续计算会有些微偏差。我们可以通过调用 print() 并使用 digits1 参数来查看确切的值:

print(x, digits = 16)

#> [1] 0.9999999999999999 2.0000000000000004You can see why R defaults to rounding these numbers; they really are very close to what you expect.

你可以看到为什么 R 默认会四舍五入这些数字;它们确实非常接近你的预期。

Now that you’ve seen why == is failing, what can you do about it? One option is to use dplyr::near() which ignores small differences:

既然你已经看到了 == 失败的原因,那你该怎么办呢?一个选项是使用 dplyr::near(),它会忽略微小的差异:

12.2.2 Missing values

Missing values represent the unknown so they are “contagious”: almost any operation involving an unknown value will also be unknown:

缺失值代表未知,所以它们是“会传染的”:几乎任何涉及未知值的操作结果也将是未知的:

NA > 5

#> [1] NA

10 == NA

#> [1] NAThe most confusing result is this one:

最令人困惑的结果是这个:

NA == NA

#> [1] NAIt’s easiest to understand why this is true if we artificially supply a little more context:

如果我们人为地提供一些上下文,就最容易理解为什么这是真的:

# We don't know how old Mary is

age_mary <- NA

# We don't know how old John is

age_john <- NA

# Are Mary and John the same age?

age_mary == age_john

#> [1] NA

# We don't know!So if you want to find all flights where dep_time is missing, the following code doesn’t work because dep_time == NA will yield NA for every single row, and filter() automatically drops missing values:

所以,如果你想查找所有 dep_time 缺失的航班,下面的代码是行不通的,因为 dep_time == NA 会对每一行都产生 NA,而 filter() 会自动丢弃缺失值:

flights |>

filter(dep_time == NA)

#> # A tibble: 0 × 19

#> # ℹ 19 variables: year <int>, month <int>, day <int>, dep_time <int>,

#> # sched_dep_time <int>, dep_delay <dbl>, arr_time <int>, …Instead we’ll need a new tool: is.na().

因此,我们需要一个新工具:is.na()。

12.2.3 is.na()

is.na(x) works with any type of vector and returns TRUE for missing values and FALSE for everything else:is.na(x) 适用于任何类型的向量,对于缺失值返回 TRUE,对于其他所有值返回 FALSE:

We can use is.na() to find all the rows with a missing dep_time:

我们可以使用 is.na() 来查找所有 dep_time 缺失的行:

flights |>

filter(is.na(dep_time))

#> # A tibble: 8,255 × 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 NA 1630 NA NA 1815

#> 2 2013 1 1 NA 1935 NA NA 2240

#> 3 2013 1 1 NA 1500 NA NA 1825

#> 4 2013 1 1 NA 600 NA NA 901

#> 5 2013 1 2 NA 1540 NA NA 1747

#> 6 2013 1 2 NA 1620 NA NA 1746

#> # ℹ 8,249 more rows

#> # ℹ 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>, carrier <chr>, flight <int>, …is.na() can also be useful in arrange(). arrange() usually puts all the missing values at the end but you can override this default by first sorting by is.na():is.na() 在 arrange() 中也很有用。arrange() 通常会将所有缺失值放在末尾,但你可以通过先按 is.na() 排序来覆盖这个默认行为:

flights |>

filter(month == 1, day == 1) |>

arrange(dep_time)

#> # A tibble: 842 × 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

#> 5 2013 1 1 554 600 -6 812 837

#> 6 2013 1 1 554 558 -4 740 728

#> # ℹ 836 more rows

#> # ℹ 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>, carrier <chr>, flight <int>, …

flights |>

filter(month == 1, day == 1) |>

arrange(desc(is.na(dep_time)), dep_time)

#> # A tibble: 842 × 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 NA 1630 NA NA 1815

#> 2 2013 1 1 NA 1935 NA NA 2240

#> 3 2013 1 1 NA 1500 NA NA 1825

#> 4 2013 1 1 NA 600 NA NA 901

#> 5 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 6 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> # ℹ 836 more rows

#> # ℹ 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>, carrier <chr>, flight <int>, …We’ll come back to cover missing values in more depth in Chapter 18.

我们将在 Chapter 18 中更深入地讨论缺失值。

12.2.4 Exercises

How does

dplyr::near()work? Typenearto see the source code. Issqrt(2)^2near 2?Use

mutate(),is.na(), andcount()together to describe how the missing values indep_time,sched_dep_timeanddep_delayare connected.

12.3 Boolean algebra

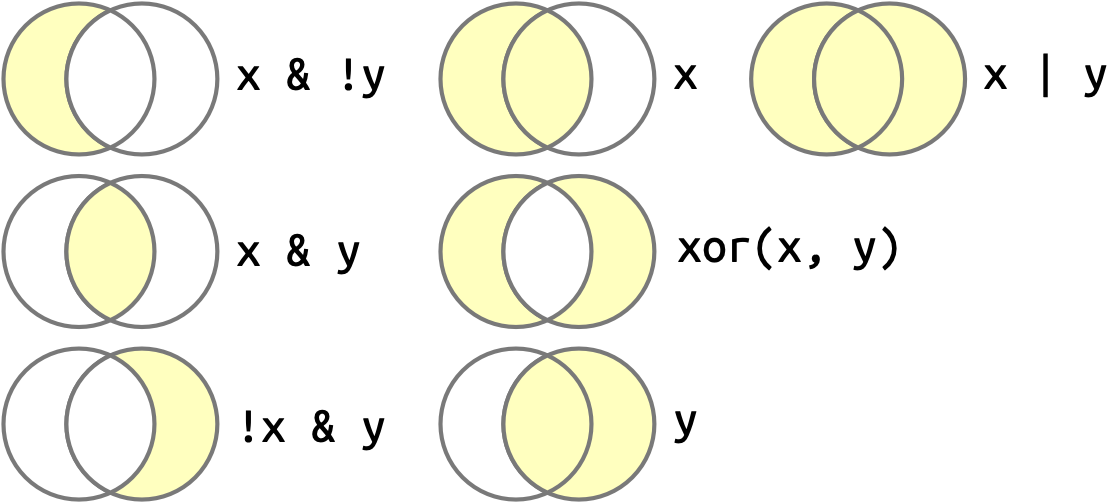

Once you have multiple logical vectors, you can combine them together using Boolean algebra. In R, & is “and”, | is “or”, ! is “not”, and xor() is exclusive or2. For example, df |> filter(!is.na(x)) finds all rows where x is not missing and df |> filter(x < -10 | x > 0) finds all rows where x is smaller than -10 or bigger than 0. Figure 12.1 shows the complete set of Boolean operations and how they work.

一旦你有了多个逻辑向量,就可以使用布尔代数将它们组合起来。在 R 中,& 是“与”,| 是“或”,! 是“非”,而 xor() 是异或(exclusive or)1。例如,df |> filter(!is.na(x)) 会找到所有 x 不缺失的行,而 df |> filter(x < -10 | x > 0) 会找到所有 x 小于 -10 或大于 0 的行。Figure 12.1 展示了完整的布尔运算集及其工作原理。

x is the left-hand circle, y is the right-hand circle, and the shaded regions show which parts each operator selects.

As well as & and |, R also has && and ||. Don’t use them in dplyr functions! These are called short-circuiting operators and only ever return a single TRUE or FALSE. They’re important for programming, not data science.

除了 & 和 |,R 还有 && 和 ||。不要在 dplyr 函数中使用它们!这些被称为短路运算符,它们只返回单个的 TRUE 或 FALSE。它们对于编程很重要,而不是数据科学。

12.3.1 Missing values

The rules for missing values in Boolean algebra are a little tricky to explain because they seem inconsistent at first glance:

布尔代数中关于缺失值的规则有点难以解释,因为它们乍一看似乎不一致:

To understand what’s going on, think about NA | TRUE (NA or TRUE). A missing value in a logical vector means that the value could either be TRUE or FALSE. TRUE | TRUE and FALSE | TRUE are both TRUE because at least one of them is TRUE. NA | TRUE must also be TRUE because NA can either be TRUE or FALSE. However, NA | FALSE is NA because we don’t know if NA is TRUE or FALSE. Similar reasoning applies for & considering that both conditions must be fulfilled. Therefore NA & TRUE is NA because NA can either be TRUE or FALSE and NA & FALSE is FALSE because at least one of the conditions is FALSE.

要理解发生了什么,可以思考一下 NA | TRUE(NA 或 TRUE)。逻辑向量中的缺失值意味着该值可能是 TRUE 或 FALSE。TRUE | TRUE 和 FALSE | TRUE 都是 TRUE,因为其中至少有一个是 TRUE。NA | TRUE 也必须是 TRUE,因为 NA 可能是 TRUE 或 FALSE。然而,NA | FALSE 的结果是 NA,因为我们不知道 NA 是 TRUE 还是 FALSE。类似的推理也适用于 &,考虑到两个条件都必须满足。因此,NA & TRUE 的结果是 NA,因为 NA 可能是 TRUE 或 FALSE;而 NA & FALSE 的结果是 FALSE,因为至少有一个条件是 FALSE。

12.3.2 Order of operations

Note that the order of operations doesn’t work like English. Take the following code that finds all flights that departed in November or December:

注意,运算顺序不像英语那样。看下面这段查找所有在 11 月或 12 月起飞的航班的代码:

flights |>

filter(month == 11 | month == 12)You might be tempted to write it like you’d say in English: “Find all flights that departed in November or December.”:

你可能会想当然地像用英语说的那样写:“查找所有在 11 月或 12 月起飞的航班。”:

flights |>

filter(month == 11 | 12)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 × 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

#> 5 2013 1 1 554 600 -6 812 837

#> 6 2013 1 1 554 558 -4 740 728

#> # ℹ 336,770 more rows

#> # ℹ 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>, carrier <chr>, flight <int>, …This code doesn’t error but it also doesn’t seem to have worked. What’s going on? Here, R first evaluates month == 11 creating a logical vector, which we call nov. It computes nov | 12. When you use a number with a logical operator it converts everything apart from 0 to TRUE, so this is equivalent to nov | TRUE which will always be TRUE, so every row will be selected:

这段代码没有报错,但似乎也没有起作用。这是怎么回事?在这里,R 首先评估 month == 11,创建了一个我们称之为 nov 的逻辑向量。然后它计算 nov | 12。当你将数字与逻辑运算符一起使用时,除了 0 之外的所有数字都会被转换为 TRUE,所以这等价于 nov | TRUE,结果将永远是 TRUE,因此所有行都会被选中:

flights |>

mutate(

nov = month == 11,

final = nov | 12,

.keep = "used"

)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 × 3

#> month nov final

#> <int> <lgl> <lgl>

#> 1 1 FALSE TRUE

#> 2 1 FALSE TRUE

#> 3 1 FALSE TRUE

#> 4 1 FALSE TRUE

#> 5 1 FALSE TRUE

#> 6 1 FALSE TRUE

#> # ℹ 336,770 more rows

12.3.3 %in%

An easy way to avoid the problem of getting your ==s and |s in the right order is to use %in%. x %in% y returns a logical vector the same length as x that is TRUE whenever a value in x is anywhere in y .

一个避免 == 和 | 排序问题的简单方法是使用 %in%。x %in% y 会返回一个与 x 长度相同的逻辑向量,当 x 中的值存在于 y 中任何位置时,该向量对应元素为 TRUE。

So to find all flights in November and December we could write:

所以要查找所有在十一月和十二月的航班,我们可以这样写:

Note that %in% obeys different rules for NA to ==, as NA %in% NA is TRUE.

注意,对于 NA,%in% 遵循与 == 不同的规则,因为 NA %in% NA 的结果是 TRUE。

This can make for a useful shortcut:

这可以成为一个有用的快捷方式:

flights |>

filter(dep_time %in% c(NA, 0800))

#> # A tibble: 8,803 × 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 800 800 0 1022 1014

#> 2 2013 1 1 800 810 -10 949 955

#> 3 2013 1 1 NA 1630 NA NA 1815

#> 4 2013 1 1 NA 1935 NA NA 2240

#> 5 2013 1 1 NA 1500 NA NA 1825

#> 6 2013 1 1 NA 600 NA NA 901

#> # ℹ 8,797 more rows

#> # ℹ 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>, carrier <chr>, flight <int>, …12.3.4 Exercises

Find all flights where

arr_delayis missing butdep_delayis not. Find all flights where neitherarr_timenorsched_arr_timeare missing, butarr_delayis.How many flights have a missing

dep_time? What other variables are missing in these rows? What might these rows represent?Assuming that a missing

dep_timeimplies that a flight is cancelled, look at the number of cancelled flights per day. Is there a pattern? Is there a connection between the proportion of cancelled flights and the average delay of non-cancelled flights?

12.4 Summaries

The following sections describe some useful techniques for summarizing logical vectors. As well as functions that only work specifically with logical vectors, you can also use functions that work with numeric vectors.

以下各节介绍了一些汇总逻辑向量的有用技巧。除了专门处理逻辑向量的函数外,你还可以使用处理数值向量的函数。

12.4.1 Logical summaries

There are two main logical summaries: any() and all(). any(x) is the equivalent of |; it’ll return TRUE if there are any TRUE’s in x. all(x) is equivalent of &; it’ll return TRUE only if all values of x are TRUE’s. Like most summary functions, you can make the missing values go away with na.rm = TRUE.

有两个主要的逻辑汇总函数:any() 和 all()。any(x) 相当于 |;如果 x 中有任何一个 TRUE,它就会返回 TRUE。all(x) 相当于 &;只有当 x 的所有值都为 TRUE 时,它才会返回 TRUE。和大多数汇总函数一样,你可以通过 na.rm = TRUE 来移除缺失值。

For example, we could use all() and any() to find out if every flight was delayed on departure by at most an hour or if any flights were delayed on arrival by five hours or more. And using group_by() allows us to do that by day:

例如,我们可以使用 all() 和 any() 来查明是否每架航班的起飞延误都不超过一小时,或者是否有任何航班的到达延误达到五小时或更长。并且使用 group_by() 允许我们按天来做这个分析:

flights |>

group_by(year, month, day) |>

summarize(

all_delayed = all(dep_delay <= 60, na.rm = TRUE),

any_long_delay = any(arr_delay >= 300, na.rm = TRUE),

.groups = "drop"

)

#> # A tibble: 365 × 5

#> year month day all_delayed any_long_delay

#> <int> <int> <int> <lgl> <lgl>

#> 1 2013 1 1 FALSE TRUE

#> 2 2013 1 2 FALSE TRUE

#> 3 2013 1 3 FALSE FALSE

#> 4 2013 1 4 FALSE FALSE

#> 5 2013 1 5 FALSE TRUE

#> 6 2013 1 6 FALSE FALSE

#> # ℹ 359 more rowsIn most cases, however, any() and all() are a little too crude, and it would be nice to be able to get a little more detail about how many values are TRUE or FALSE. That leads us to the numeric summaries.

然而,在大多数情况下,any() 和 all() 有点过于粗略,如果能更详细地了解有多少值是 TRUE 或 FALSE 会更好。这就引出了数值汇总。

12.4.2 Numeric summaries of logical vectors

When you use a logical vector in a numeric context, TRUE becomes 1 and FALSE becomes 0. This makes sum() and mean() very useful with logical vectors because sum(x) gives the number of TRUEs and mean(x) gives the proportion of TRUEs (because mean() is just sum() divided by length()).

当你在数值上下文中使用逻辑向量时,TRUE 会变成 1,FALSE 会变成 0。这使得 sum() 和 mean() 在处理逻辑向量时非常有用,因为 sum(x) 给出了 TRUE 的数量,而 mean(x) 给出了 TRUE 的比例(因为 mean() 就是 sum() 除以 length())。

That, for example, allows us to see the proportion of flights that were delayed on departure by at most an hour and the number of flights that were delayed on arrival by five hours or more:

例如,这让我们可以查看起飞延误最多一小时的航班比例,以及到达延误五小时或以上的航班数量:

flights |>

group_by(year, month, day) |>

summarize(

proportion_delayed = mean(dep_delay <= 60, na.rm = TRUE),

count_long_delay = sum(arr_delay >= 300, na.rm = TRUE),

.groups = "drop"

)

#> # A tibble: 365 × 5

#> year month day proportion_delayed count_long_delay

#> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 0.939 3

#> 2 2013 1 2 0.914 3

#> 3 2013 1 3 0.941 0

#> 4 2013 1 4 0.953 0

#> 5 2013 1 5 0.964 1

#> 6 2013 1 6 0.959 0

#> # ℹ 359 more rows12.4.3 Logical subsetting

There’s one final use for logical vectors in summaries: you can use a logical vector to filter a single variable to a subset of interest. This makes use of the base [ (pronounced subset) operator, which you’ll learn more about in Section 27.2.

在汇总中,逻辑向量还有一个最终用途:你可以使用逻辑向量将单个变量筛选到感兴趣的子集。这利用了 R base 的 [(发音为 subset)运算符,你将在 Section 27.2 中学到更多相关内容。

Imagine we wanted to look at the average delay just for flights that were actually delayed. One way to do so would be to first filter the flights and then calculate the average delay:

假设我们只想看实际延误航班的平均延误时间。一种方法是先筛选出这些航班,然后计算平均延误时间:

flights |>

filter(arr_delay > 0) |>

group_by(year, month, day) |>

summarize(

behind = mean(arr_delay),

n = n(),

.groups = "drop"

)

#> # A tibble: 365 × 5

#> year month day behind n

#> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 32.5 461

#> 2 2013 1 2 32.0 535

#> 3 2013 1 3 27.7 460

#> 4 2013 1 4 28.3 297

#> 5 2013 1 5 22.6 238

#> 6 2013 1 6 24.4 381

#> # ℹ 359 more rowsThis works, but what if we wanted to also compute the average delay for flights that arrived early? We’d need to perform a separate filter step, and then figure out how to combine the two data frames together3. Instead you could use [ to perform an inline filtering: arr_delay[arr_delay > 0] will yield only the positive arrival delays.

这样做是可行的,但如果我们还想计算提早到达航班的平均延误时间呢?我们就需要执行一个单独的筛选步骤,然后想办法将两个数据框合并在一起3。相反,你可以使用 [ 来执行内联筛选:arr_delay[arr_delay > 0] 将只产生正的到达延误时间。

This leads to:

这会得到:

flights |>

group_by(year, month, day) |>

summarize(

behind = mean(arr_delay[arr_delay > 0], na.rm = TRUE),

ahead = mean(arr_delay[arr_delay < 0], na.rm = TRUE),

n = n(),

.groups = "drop"

)

#> # A tibble: 365 × 6

#> year month day behind ahead n

#> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 32.5 -12.5 842

#> 2 2013 1 2 32.0 -14.3 943

#> 3 2013 1 3 27.7 -18.2 914

#> 4 2013 1 4 28.3 -17.0 915

#> 5 2013 1 5 22.6 -14.0 720

#> 6 2013 1 6 24.4 -13.6 832

#> # ℹ 359 more rowsAlso note the difference in the group size: in the first chunk n() gives the number of delayed flights per day; in the second, n() gives the total number of flights.

同时注意组大小的差异:在第一个代码块中,n() 给出的是每天延误的航班数量;在第二个代码块中,n() 给出的是总航班数量。

12.4.4 Exercises

- What will

sum(is.na(x))tell you? How aboutmean(is.na(x))? - What does

prod()return when applied to a logical vector? What logical summary function is it equivalent to? What doesmin()return when applied to a logical vector? What logical summary function is it equivalent to? Read the documentation and perform a few experiments.

12.5 Conditional transformations

One of the most powerful features of logical vectors are their use for conditional transformations, i.e. doing one thing for condition x, and something different for condition y. There are two important tools for this: if_else() and case_when().

逻辑向量最强大的特性之一是它们在条件转换中的应用,即针对条件 x 做一件事,针对条件 y 做另一件事。有两个重要的工具可以实现这一点:if_else() 和 case_when()。

12.5.1 if_else()

If you want to use one value when a condition is TRUE and another value when it’s FALSE, you can use dplyr::if_else()4. You’ll always use the first three argument of if_else(). The first argument, condition, is a logical vector, the second, true, gives the output when the condition is true, and the third, false, gives the output if the condition is false.

如果你想在条件为 TRUE 时使用一个值,而在条件为 FALSE 时使用另一个值,你可以使用 dplyr::if_else()4。你总是会使用 if_else() 的前三个参数。第一个参数 condition 是一个逻辑向量,第二个参数 true 给出条件为真时的输出,第三个参数 false 给出条件为假时的输出。

Let’s begin with a simple example of labeling a numeric vector as either “+ve” (positive) or “-ve” (negative):

让我们从一个简单的例子开始,将一个数值向量标记为“+ve”(正数)或“-ve”(负数):

There’s an optional fourth argument, missing which will be used if the input is NA:

还有一个可选的第四个参数 missing,当输入为 NA 时会使用这个参数:

if_else(x > 0, "+ve", "-ve", "???")

#> [1] "-ve" "-ve" "-ve" "-ve" "+ve" "+ve" "+ve" "???"You can also use vectors for the true and false arguments. For example, this allows us to create a minimal implementation of abs():

你也可以为 true 和 false 参数使用向量。例如,这允许我们创建一个 abs() 的最小化实现:

if_else(x < 0, -x, x)

#> [1] 3 2 1 0 1 2 3 NASo far all the arguments have used the same vectors, but you can of course mix and match. For example, you could implement a simple version of coalesce() like this:

到目前为止,所有的参数都使用了相同的向量,但你当然可以混合搭配。例如,你可以像这样实现一个 coalesce() 的简单版本:

You might have noticed a small infelicity in our labeling example above: zero is neither positive nor negative. We could resolve this by adding an additional if_else():

你可能已经注意到我们上面标签示例中的一个小瑕疵:零既不是正数也不是负数。我们可以通过添加一个额外的 if_else() 来解决这个问题:

This is already a little hard to read, and you can imagine it would only get harder if you have more conditions. Instead, you can switch to dplyr::case_when().

这已经有点难读了,你可以想象,如果你有更多的条件,情况只会变得更糟。因此,你可以转而使用 dplyr::case_when()。

12.5.2 case_when()

dplyr’s case_when() is inspired by SQL’s CASE statement and provides a flexible way of performing different computations for different conditions. It has a special syntax that unfortunately looks like nothing else you’ll use in the tidyverse. It takes pairs that look like condition ~ output. condition must be a logical vector; when it’s TRUE, output will be used.

dplyr 的 case_when() 受到 SQL 的 CASE 语句的启发,提供了一种为不同条件执行不同计算的灵活方式。它有一种特殊的语法,不幸的是,这与你在 tidyverse 中使用的其他任何东西都不一样。它接受形如 condition ~ output 的配对。condition 必须是一个逻辑向量;当它为 TRUE 时,将使用 output。

This means we could recreate our previous nested if_else() as follows:

这意味着我们可以像下面这样重新创建我们之前的嵌套 if_else():

This is more code, but it’s also more explicit.

这需要更多的代码,但它也更明确。

To explain how case_when() works, let’s explore some simpler cases. If none of the cases match, the output gets an NA:

为了解释 case_when() 的工作原理,让我们探讨一些更简单的情况。如果没有一个条件匹配,输出将得到一个 NA:

case_when(

x < 0 ~ "-ve",

x > 0 ~ "+ve"

)

#> [1] "-ve" "-ve" "-ve" NA "+ve" "+ve" "+ve" NAUse .default if you want to create a “default”/catch all value:

如果你想创建一个“默认”或“包罗万象”的值,请使用 .default:

case_when(

x < 0 ~ "-ve",

x > 0 ~ "+ve",

.default = "???"

)

#> [1] "-ve" "-ve" "-ve" "???" "+ve" "+ve" "+ve" "???"And note that if multiple conditions match, only the first will be used:

并且请注意,如果多个条件匹配,只有第一个会被使用:

case_when(

x > 0 ~ "+ve",

x > 2 ~ "big"

)

#> [1] NA NA NA NA "+ve" "+ve" "+ve" NAJust like with if_else() you can use variables on both sides of the ~ and you can mix and match variables as needed for your problem. For example, we could use case_when() to provide some human readable labels for the arrival delay:

就像 if_else() 一样,你可以在 ~ 的两边使用变量,并且可以根据你的问题需要混合和匹配变量。例如,我们可以使用 case_when() 为到达延迟提供一些人类可读的标签:

flights |>

mutate(

status = case_when(

is.na(arr_delay) ~ "cancelled",

arr_delay < -30 ~ "very early",

arr_delay < -15 ~ "early",

abs(arr_delay) <= 15 ~ "on time",

arr_delay < 60 ~ "late",

arr_delay < Inf ~ "very late",

),

.keep = "used"

)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 × 2

#> arr_delay status

#> <dbl> <chr>

#> 1 11 on time

#> 2 20 late

#> 3 33 late

#> 4 -18 early

#> 5 -25 early

#> 6 12 on time

#> # ℹ 336,770 more rowsBe wary when writing this sort of complex case_when() statement; my first two attempts used a mix of < and > and I kept accidentally creating overlapping conditions.

在编写这类复杂的 case_when() 语句时要小心;我最初的两次尝试混合使用了 < 和 >,结果不小心创建了重叠的条件。

12.5.3 Compatible types

Note that both if_else() and case_when() require compatible types in the output. If they’re not compatible, you’ll see errors like this:

请注意,if_else() 和 case_when() 都要求输出中的类型是兼容的。如果它们不兼容,你会看到类似这样的错误:

Overall, relatively few types are compatible, because automatically converting one type of vector to another is a common source of errors. Here are the most important cases that are compatible:

总的来说,相对较少的类型是兼容的,因为自动将一种类型的向量转换为另一种类型是错误的常见来源。以下是兼容的最重要情况:

Numeric and logical vectors are compatible, as we discussed in Section 12.4.2.

数值向量和逻辑向量是兼容的,正如我们在 Section 12.4.2 中讨论的那样。Strings and factors (Chapter 16) are compatible, because you can think of a factor as a string with a restricted set of values.

字符串和因子(Chapter 16)是兼容的,因为你可以把因子看作是一组受限制的字符串。Dates and date-times, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 17, are compatible because you can think of a date as a special case of date-time.

日期和日期时间(我们将在 Chapter 17 中讨论)是兼容的,因为你可以把日期看作是日期时间的一种特殊情况。NA, which is technically a logical vector, is compatible with everything because every vector has some way of representing a missing value.NA,严格来说是一个逻辑向量,它与所有类型都兼容,因为每个向量都有表示缺失值的方式。

We don’t expect you to memorize these rules, but they should become second nature over time because they are applied consistently throughout the tidyverse.

我们不期望你记住这些规则,但随着时间的推移,它们应该会成为你的第二天性,因为它们在整个 tidyverse 中都是一致应用的。

12.5.4 Exercises

A number is even if it’s divisible by two, which in R you can find out with

x %% 2 == 0. Use this fact andif_else()to determine whether each number between 0 and 20 is even or odd.Given a vector of days like

x <- c("Monday", "Saturday", "Wednesday"), use anif_else()statement to label them as weekends or weekdays.Use

if_else()to compute the absolute value of a numeric vector calledx.Write a

case_when()statement that uses themonthanddaycolumns fromflightsto label a selection of important US holidays (e.g., New Years Day, 4th of July, Thanksgiving, and Christmas). First create a logical column that is eitherTRUEorFALSE, and then create a character column that either gives the name of the holiday or isNA.

12.6 Summary

The definition of a logical vector is simple because each value must be either TRUE, FALSE, or NA. But logical vectors provide a huge amount of power. In this chapter, you learned how to create logical vectors with >, <, <=, >=, ==, !=, and is.na(), how to combine them with !, &, and |, and how to summarize them with any(), all(), sum(), and mean(). You also learned the powerful if_else() and case_when() functions that allow you to return values depending on the value of a logical vector.

逻辑向量的定义很简单,因为每个值必须是 TRUE、FALSE 或 NA 之一。但逻辑向量提供了巨大的能力。在本章中,你学习了如何使用 >、<、<=、>=、==、!= 和 is.na() 创建逻辑向量,如何使用 !、& 和 | 组合它们,以及如何使用 any()、all()、sum() 和 mean() 对它们进行汇总。你还学习了强大的 if_else() 和 case_when() 函数,它们允许你根据逻辑向量的值返回不同的值。

We’ll see logical vectors again and again in the following chapters. For example in Chapter 14 you’ll learn about str_detect(x, pattern) which returns a logical vector that’s TRUE for the elements of x that match the pattern, and in Chapter 17 you’ll create logical vectors from the comparison of dates and times. But for now, we’re going to move onto the next most important type of vector: numeric vectors.

在接下来的章节中,我们将反复看到逻辑向量。例如,在 Chapter 14 中,你将学习 str_detect(x, pattern),它会返回一个逻辑向量,对于 x 中匹配 pattern 的元素,该向量为 TRUE;在 Chapter 17 中,你将通过比较日期和时间来创建逻辑向量。但现在,我们将转向下一种最重要的向量类型:数值向量。

R normally calls print for you (i.e.

xis a shortcut forprint(x)), but calling it explicitly is useful if you want to provide other arguments.↩︎That is,

xor(x, y)is true if x is true, or y is true, but not both. This is how we usually use “or” In English. “Both” is not usually an acceptable answer to the question “would you like ice cream or cake?”.↩︎We’ll cover this in Chapter 19.↩︎

dplyr’s

if_else()is very similar to base R’sifelse(). There are two main advantages ofif_else()overifelse(): you can choose what should happen to missing values, andif_else()is much more likely to give you a meaningful error if your variables have incompatible types.↩︎